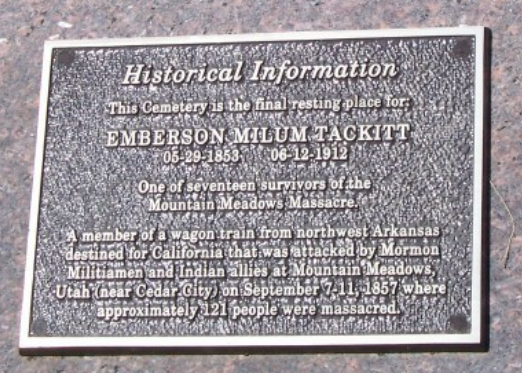

FindAGrave.com Memorial # 8426822

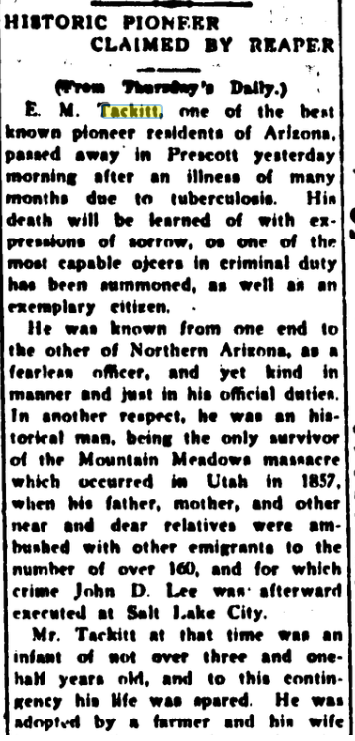

Arizona Miner, Ft. Whipple, AZ

June 19, 1912, Page 8

Mountain Meadows Massacre:

A Story of Allred Descendants Who Survived

by Linda Allred Cooper

Allred Lineage for Emberson and William Tackitt: Armilda Miller, Sarah Allred, John Allred, Solomon Allred, Solomon Allred

Information about Emberson is at the end of this page. Click here to see information about his brother William.

About 35 miles southwest of Cedar City, Utah, is a quiet meadow, peaceful and serene today. It was not so on the morning of September 11, 1857. Note: the reasons for the Mountain Meadows Massacre and who did the killings has been discussed, debated, analyzed and argued about ever since it happened. I am not going to get into that discussion with this article – but, instead, focus on the story of what happened and two little boys, Allred descendants, who survived the violence.

Armilda Miller was born in Overton County, Tennessee, about 1835, the daughter of Emberson Miller and his wife Sarah Allred. The family moved to Johnson County, Arkansas, when Armilda was a young girl. It was there she met and married a young Methodist minister, Pleasant Tackitt, about 1852. By the summer of 1857, Pleasant and Armilda had two sons, Emberson Milum born May 29, 1853, and William Henry born January 20, 1856.

The 1849 discovery of gold in California had lured many to travel west. Tales of wealth fanned by stories told by travelers passing through grew grander and grander with each telling; luring many to join a wagon train heading west. Documentation of the day tells us there were at least four wagon trains (also called Companies) organized in Arkansas by Alexander Fancher and John T. Baker in April 1857. One of these Companies consisted of the interrelated Cameron, Jones, Tackitt and Miller families of Johnson County.

Unlike the romantic movie version of wagon train travel with singing cowboys and happy, smiling pioneers, the reality was harsh and grueling. The wagon train leader, in this case Fancher, pushed to keep the wagons moving every day. Depending on the weather and terrain, the wagons would travel 10 to 20 miles each day. No meal or bathroom breaks – everyone just kept walking, riding only when they had to in an attempt to keep the wagons as light at possible for the pack animals. In the evenings, fires would be built and meals cooked and consumed, then everyone was up and prepared to travel again by the break of dawn.

Indian attacks were common. There was no time for bad health or illness. Wolves, bears, coyotes and other animals stalked the livestock (and any small children who wandered too far from their parents). Pleasant and Armilda Tackitt were traveling with two small boys: Emberon who was four years old and William who was 16 months old.

September 1, 1857, found the Fancher wagon train some seventy miles north of Mountain Meadows. Supplies were low and the train members tried buying and trading with the local residents, both white and Indian but few would agree to sell to them. The wagon train arrived in Cedar City on Friday, September 4, and inquiries were made about a place where they could stop to rest for a few days, a place where they could find water and grazing land for their animals. Two days later, the wagon train entered Mountain Meadows.

Survivor testimony and stories tell us the last of the wagons entered the Meadows after dark and the travelers were so weary they failed to organize a corral. The Meadows was bordered by ravines on the east and south, low hills on the west and volcanic ridges on the north. The travelers probably felt these natural formations would keep the cattle, horses and other animals from wandering too far and they settled in for the night. As the last wagons pulled into the campsite just before dawn the next morning, the wagon train came under attack. A child who survived the attack later wrote “Our party was just sitting down to a breakfast of quail and cottontail rabbits when a shot rang out from a nearby gully and one of the children toppled over, hit by the bullet. The deadly barrage struck down between ten and fifteen victims killing seven of them. Three of the wounded men were taken out of the fight and died within days.”

Another witness stated “the firing kept up until after daylight, all of half an hour, when it ceased.” In government testimony later, then four-year-old Emberson Tackitt told of the heroism of his aunt Eloah Angeline Tackitt Jones as she fought alongside the men, using the gun of one of the fallen emigrants. The wagon train’s livestock were rounded up by the attackers and taken away. Guards were posted by the attackers to prevent the emigrants from getting water. The victims were trapped and left to dig pits to shelter the women, children, and wounded while wagons were circled to provide what little protection they could.

Monday and again Tuesday, the wagon train came under attack but fought back bravely. The few details of the five-day siege recalled by the surviving children only began to capture the horror of life inside the wagon fort. Huddled in the newly dug pits, the terrorized women and children were relatively safe. The smell of dead animals and unburied corpses filled the air. Victims suffered from fear, hunger and thirst.

The victims did their best, but the defenses had their limits. Wagon wheels were chained together and trenches were dug surrounding them. Pits were dug deeper inside the wagon circle so survivors could hide but survivor Sarah Baker, three years old at the time, recalled sitting on her father’s lap as a bullet tore through the lower part of her left ear, marking her for life and wounding her father.

Another attack came Tuesday night and again Wednesday. Attacks followed on Thursday morning. While bullets were flying, two of the men from the wagon train left the encircled wagons to run to the nearby spring to fill buckets. “The bullets flew around them thick and fast but they got into their corral in safety.” On Friday, September 11, two men from a local settlement appeared on the horizon and were allowed to enter the wagon fort. The wagon train survivors endured five days under siege and finally heard they were going to be rescued. They were told if they would lay down their arms, the local militia would escort them to safety. They were then separated into three groups: the wounded and youngest children led the way in two wagons, the women and older children walked behind, and the men, each escorted by an armed guard brought up the rear. They were walked more than a mile to the rim of The Great Basin when a single shot was fired which was the signal to all of the armed guards. Each escort turned and shot his man. More attackers jumped out of the brush lining the trail and murdered the women and older children. The wounded in the wagons were killed. The children survivors said that within five minutes it was all over. All of the wagon train members were dead except for 17 small children, all under the age of 7, whom the attackers apparently felt were too young to tell the story.

Emberson and William Tackitt were among those 17 children who survived the massacre. They were taken to Cedar City and given to the family of John M. Higbee, although the brothers were soon separated when William was taken away to live with the family of Elias Morris. In 1859 the U.S. Government finally sent investigators to Utah and the surviving children were gathered up and returned to their families. Emberson and William were claimed and taken back to Arkansas to be raised by their maternal grandparents, Emberson and Sarah Allred Miller.

Per the Deseret News, stories handed down by Emberson’s descendants tell us he remembered “one of the Indians had him and were threatening to kill him but he offered them his pants and his boots if they would spare his life. He was surprised when they went down to the river and washed off the war paint and he discovered they were white men”. Emberson also “remembered seeing people wearing his mother’s clothing and using family items taken after the massacre”.

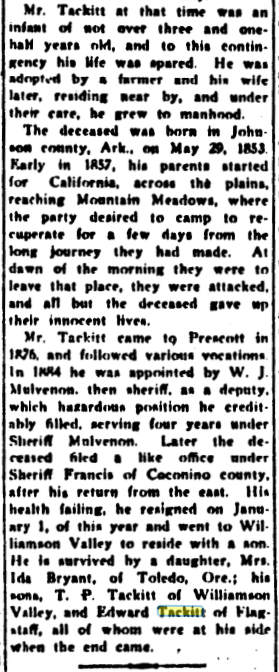

Two newspaper articles tell us Emberson and William grew up to have long and fruitful lives. From the Prescott Journal Miner of June 15, 1912:

Popular Pioneer is Laid to Rest. The funeral yesterday of E. M. Tackitt, one of the best known deputy Sheriffs in the Southwest, took place from Ruffner’s Chapel in this city, and was attended by many friends. Religious services were conducted by Rev. Marshall of the Baptist church and the occasion was a sad one to many friends of the deceased. As a tribute to the memory of Mr. Tackitt, the pall bearers were selected from the exempts list Tough Hose Co., of which he had been a member a last quarter century ago, and were J. W. Wilson, R. N. Fredericks, Thomas Scholey, Adolph Moser, B. H. Smith, and Roland Mosher. Interment was in the Citizens’ cemetery.

Prescott Journal Miner of June 13, 1912, Page 52:

(As you read this article, you will see the reporter did not do a good job researching and made mistakes with a couple of the facts. Emberson was not the sole survivor of the massacre. He was not raised by a farmer in Utah but, instead, was raised by his maternal grandparents in Arkansas.)

Historic Pioneer Claimed by Reaper. Sole Survivor of Mountain Meadow Massacre Cut Down By Deadly White Plague. E. M. Tackitt, one of the best known pioneer residents of Arizona, passed away in Prescott yesterday morning after an illness of many months due to tuberculosis. His death will be learned of with expressions of sorrow, as one of the most capable officers in criminal duty has been summoned, as well as an exemplary citizen. He was known from one end to the other of Northern Arizona, as a fearless officer, and yet kind in manner and just in his official duties. In another respect, he was historical man, being the only survivor of the Mountain Meadows Massacre which occurred in Utah in 1857, when his father, mother and other near and dear relatives were ambushed with other emigrants to the number of over 160 (actually 121), and for which crime John D. Lee was afterward executed. Mr. Tackitt at that time was an infant of not over three and one-half years old, and to the contingency his life was spared. He was adopted by a farmer and his wife later, residing nearby, and under their care he grew to manhood. The deceased was born in Johnson Co., Ark., on May 29, 1853. Early in 1857, his parents started for California, across the plains, reaching Mountain Meadows, where the party desired to camp to recuperate for a few days from the long journey they had made. At dawn of the morning they were to leave that place, they were attacked, and all but the deceased gave up their innocent lives. Mr. Tackitt came to Prescott in 1876, and followed various vocations. In 1884 he was appointed by W. J. Malvenon, then sheriff, as a deputy, which hazardous position he creditably filled, serving four years under Sheriff Malvenon. Later the deceased filled a like office under Sheriff Francis of Coconino County, after his return from the east. His health failing, he resigned on January 1, 1912, of this year and went to Williamson Valley to reside with a son. He is survived by a daughter, Mrs. Ida Bryant, of Toledo, Ore. his sons, T. P. Tackitt of Williamson Valley, and Edward Tackitt of Flagstaff, all of whom were at his bedside when the end came.