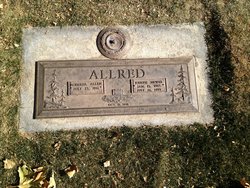

Joseph Newell ALLRED

Joseph Newell ALLRED

Allred Lineage: Joseph Newell, Joseph Newberry, Edsil Myron, Joseph Anderson, Isaac, William, Thomas, Solomon born 1680 England

Born: 01/15/1915

Died: 07/29/1997

Submitted by: Sharon Allred Jessop 05/19/1999

January 15, 1915

Little Abe

Nostalgic memories were triggered by Dr. Knowles in his romance of horses to a time and place when a man bought a horse to help support himself vs. buying horses to relieve frustration. Little Abe was born to see both. We called him Little Abe because his sire was Little Man by Oklahoma Star and because the neighbor’s kid envied him so.

Nostalgic memories were triggered by Dr. Knowles in his romance of horses to a time and place when a man bought a horse to help support himself vs. buying horses to relieve frustration. Little Abe was born to see both. We called him Little Abe because his sire was Little Man by Oklahoma Star and because the neighbor’s kid envied him so.

At three years Little Abe was a mighty handsome quarter horse, but because he had more muscle than bone and interfered somewhat, I gelded him and sent him up to my kid brother, Tex (Edsil), to be introduced to range work. Tex worked on a desert range in Northwestern Arizona and the few mountains that broke up the terrain had been run over by prospectors for a hundred years but about all that was left now were the mounds and empty shafts and a few descendants of their pack burros. Little Abe was still green that fall day when Tex, on a routine circuit, spied one of these descendants, a two year old mule, upwind a short piece in a small clearing in the cholla cactus and mesquite.

Now a range mule, properly broke, is a right valuable critter and Little Abe needed experience, so Tex leaned over and tightened the cinch, uncoiled his old nylon (by gosh, all he had left was 20 feet), eased Little Abe up to the edge of the clearing and broke in on top of that wild mule like a half ton bolt. Before the jack could get into the brush a neat little loop sailed over his big ears, but before the noose swished over his long nose, that wild mule lifted his forelegs like a bird in flight and by the time he had reached the end of the rope, Tex had a wild mule by one hind foot.

Now this was downright inconvenient for he could not drag him ten miles to the corral by one leg and he would have to be hog tied to get the rope up on his head but to get that mule stretched out long enough to get him tied proved to be quite a problem..for half a dozen times Tex and Little Abe drove by and jerked him off his feet and swirled him through the air like a rock on a string, but each time that jack would land with at least one foot on the ground, violently kicking against the nylon and beating a hot line of welts along Little Abe’s right side and Tex’s leg. By now Tex thought it might be better to get loose from the mule and he tried giving him slack and running the rope off but he had a figure eight over the fetlock and the old rope wouldn’t spring loose, so he started looking for another way out, and seeing a small sturdy old mesquite with a fork about shoulder height, he drug that jack over by the mesquite and, with a little maneuvering, got the rope flipped through the fork, and with Little Abe on one side of the tree and the jack on the other, he pulled him up to where that jack’s hind end butted up to the mesquite trunk and his hind leg was firmly lodged in the fork. Now, it was only a matter of easing Little Abe up the rope while he reeded in the slack until he had that mule’s foot dallied up to about one foot of the saddle horn, then, by releasing the horn loop, Tex got down, and with the free end of the lariat, haltered a much subdued wild mule.

While Tex caught his breath, and before cutting the rope loose from the foot, he took in the picture--a foam-streaked, green colt with a quarter of a wild mule up in his face, leaning through a fork of a mesquite, rolling his nostrils and flicking his ears to and fro, holding a taut line. He grinned, “Little Abe, you got the makings of a rope horse!”

For a Horse

This tale begins in February 1981. Roberta had flown to Sunnyvale to be with Marlin and Lisa to help indoctrinate our newest granddaughter, Melissa, into family life. Loneliness started when I returned home from the airport and by the third day my yearning for something new was getting strong. (Winter weather limited outdoor activities.) Then, out of my solitary reminiscing, came thoughts of Max Nichols.

Max was a classmate in veterinary school and I hadn’t seen him for years. I didn’t even know if he

was alive. I had heard that he had had a heart attack and was living in Sanpete County. Max was two years ahead of me in vet school and a very likeable Mormon boy. Occasional rumors over the past 25 years indicated that Max had abdicated his veterinary career goals to raise and show horses. Perhaps a visit with Max would help ease the weight of loneliness.

Through the telephone I located Mary Nichols, his wife, and found where Max kept his chariot racing team and when he would be apt to be there at a friend’s in northeast Mt. Pleasant. I had a nice, pleasant visit with Max who, seemingly, had made a remarkable recovery from open-heart, by-pass surgery two years before. He told me of his efforts in chariot racing and their hopes to raise $7,000.00 to buy one-fourth interest in a “Futurity Colt” with someone in Salt Lake. He also mentioned a neighbor, Tom Brotherson, who had a surplus of half-Tennessee Walker colts for sale. Now this interested me more than race horses and I told Max that if he would trade for a Walker I would buy it from him. I saw Max at the Payson race track the next Saturday and he informed me that Tom wouldn’t trade but would sell cheap, so I called Tom and made an appointment to meet him at his pasture between Fairview and Mt. Pleasant the next week

The visit to Tom Brotherson’s pasture was somewhat of a trial. It took two hours to get most of the mares and colt herd into his makeshift corral and to catch three of his half-wild, unbroken colts. We waded around in six inches of melting snow with buckets of grain and flakes of hay, trying to coax them through three fields and into his barn lot. The first two colts were for a buyer in Salt Lake who would pick them up later. The third one, the best of the rest, I could have for $450.00.

Well, I didn’t care much for this one-half Appaloosa and mostly white with chestnut marking --but he was the only one of age and size to start breaking and so I agreed to take him. The only thing I liked about him was his sire, a nice large Tennessee Walker. Tom was to deliver him after the next Saturday horse sale at which I hoped to sell old Cinnamon for about $600.00. Tom delivered the colt he called Chief, Saturday afternoon, and I paid him $450.00 and then rode down to the sale barn in Spanish Fork and, to my dismay, collected only $375.00 for Cinnamon. The price of horses had dropped drastically in the previous week and I was embarrassed and chagrined. I had picked up Roberta at the airport the night before and had hoped for a pleasant surprise for her as I hoped that Chief would make a pleasure horse “par-excellent.”

Chief turned out to be wilder than a deer. I had to leave a long rope trailing from his halter to catch him and it was nearly two months before I could get up to curry or pet him. Then I saw a horse trainer of Payson advertise, “Break and train for $35.00 per week, plus feed.” I sent Chief and Dolly, a filly from my brother Earl, to Bob Davis to be gentled and ridden. After $200.00 and feed for them, I brought them home with the responsibility to keep riding them to keep them gentle. This we managed to do fairly well. I had them shod two times during the summer and even got Roberta to ride Dolly a time or two. She seemed to be the most gentle and stable of the two. Chief was still flighty, especially with children and strangers, and so I usually rode him.

In August, while Roberta was in Farr West, helping Emmalou indoctrinate Alisa into the Penrod and Allred families, I stayed to do chores and attend BYU Education week. Glancing thru the evening Daily Herald I saw an old horse van for sale for $575.00. As the van was in American Fork, I phoned Bob and asked him to check it out for me and if he thought it a good buy to phone me back the next night. “It’s a good buy,” said Bob, so by phone I agreed to put a down payment to hold it until the end of the week. (I didn’t want to miss any Education Week classes.) But first I called Roberta to tell her of my intentions. She seemed agreeable. It sounded like a bargain. Horse trailers were in the neighborhood of $2000.00.

The next week Roberta and I drove to American Fork to pick up the van. It was a 1951 Ford, one ton, truck with a homemade van with three horse stalls built on it, a genuine antique to drive. It’s vintage and two-tone color of blue and white gave it such a character that we dubbed it “Old Blue.” By the time I had it licensed in my name and a safety check it cost another $200.00.

Trips to Maryland and Arizona in October and cold weather terminated my horse activities until January when I noticed in the Nebo School District’s Continuation Education Bulletin a class in Dressage that was being offered. This was the stimulus I needed to get me working with the horses again and so I inquired by phone and finding us eligible to enter the beginners class, I enrolled Chief and myself for eight once-a-week classes of one hour for $30.00, to begin in February. I took Chief because he seemed to be the better of the two to load in Old Blue and also the better to learn and remember. I had fixed a loading chute next to the corral and had fed the ponies in Old Blue several times.

It took a lot of work to get Old Blue to start for we were having occasional sub-zero nights, but by worry and recharging batteries and placing a light bulb next to the battery at night I was able to get Old Blue to run. The first two mornings I left with the temperature in the mid teens and it hasn’t been above freezing since. I leave by 8:00 a.m. each Saturday morning and drive to the Spanish Fork Fair Grounds for the lessons and return between 10:00 and 11:00 a.m. My instructor is Mrs. Mary Ann James, a mother with at least two sons, a teenager and a pre-schooler. She is a lover of horses, dedicated to learning and riding. She has been in Dressage learning and riding, for three or four years, but has ridden horses all her life. As a teacher she is very patient and pleasant and quick to encourage and praise when the horse or you “do it right.”

Dressage is diametrically opposed to all my previous experience and habits and I find it somewhat difficult to learn and do. It would be wiser to start this training without any previous experience in riding. Actually, I believe the horse is learning his part faster than I am, but I believe that this is a more refined and higher lever of horsemanship and therefore I hope to continue. It requires more dedication and persistence and offers a life-long challenge, as they say the best ones are continuing to improve and it is a horse-rider team which takes six of more years to even reach the field of competition.

Payson, UT, 25 Mar 1982

An Axe to Grind

I do not remember my first introduction to the axe. It was a familiar household tool in those days and probably it was watching Father chop wood for the kitchen stove. Later, having the chore of carrying in the stove wood and then the struggle of mastering the axe for it became my assignment to keep the wood box supplied until I left home to go to college. This chore was often a challenge, sometimes exciting, sometimes boring, but always essential, for I never wanted to see my mother trying to chop wood. It wasn’t so bad to see Father having to knock out a few chunks of wood in an emergency for he seemed to do it with ease.

How to sharpen and use an axe as a Boy Scout was a lark for we all were using the axe at the family woodpile by the time we entered scouting and our first fund raising project as scouts was to take the team and wagon into the foothills of the Graham Mountains and bring back a cord and a half of mesquite wood per team, to furnish fuel for the Central Grammar School.

Wrestling wood from a mesquite thicket was exciting to us. We had to learn how to avoid the thorns and reach the larger limbs and trunks that were dead or dying for they produced the best wood and were the easiest to cut.

In the valley it was cottonwood trees that furnished most of our wood. It was plentiful and easy to cut. One Christmas holiday from college, J.M. Smith gave me the opportunity to trim the cottonwood trees that grew along the lane to one of his farms. This gave me ten days at $1.50 and it was sure appreciated. The limbs fell into his fields where the cows and horses ate the smaller twigs and the bark from the larger limbs.

The wood that was the most fun to chop was juniper. Each summer I worked for Uncle Alva Porter in Heber. We would spend the last ten days hauling in his winter wood. We’d pull the dead juniper down with a team and haul a wagon load in each day and I would chop some up for the stove. Juniper is easy to chop and split and has a most pleasant, fragrant odor.

I still enjoy chopping wood, now, after 45 years. I go each summer into the forest of BLM lands and bring out four to five cords of cedar or quaking aspen or oak for our winter fuel. I try to keep a one year supply ahead. Now I use a chain saw to cut the wood into stove length but I still use the old single blade plum axe that I’ve had for over 20 years. It has gone thru about half a dozen handles. I enjoy working with a good sharp axe.

If I Could be a Boy Again

If I could be a boy again I’d sure do it different! Growing up is such an easy thing if we take time to think. I didn’t think about other people -- they are so important -- I just thought about myself.

Everybody seemed to like my Dad. He was a wonderful dad but I didn’t think to ask him what he did or said to make friends until 50 years later. He said, “You have to be a friend to make friends.” and many friends are so much fun. I didn’t ask him how boys grow up to be men or integrity, or how boys should control or direct the biological urges that make growing up so hard.

If I could be a boy again I would ask him all the questions I could think of about his parents and grandparents, for now there is no one to ask about them. How did great grandparents live and why did they move and move?

If I could be a boy again I would be a “mama’s boy.” Mother’s do so much for boys but mother’s don’t last long enough. A cheerful boy that looks for things to do to help his mother brings joy to more than two and memories of mother are so precious. I would like them all to be happy ones.

After I graduated from high school I asked Mother to make a special quilt for me to use like a bedroll. It was made from old overalls on both sides and filled with old cotton flannel blankets inside. It was three times heavy. I used it as a saddle blanket and bed roll on a 225 mile horseback ride. She worked hard to make it, just for me.

If I could be a boy again I’d try hard to be patient and kind to sisters. They need a brother for a friend, one who is an example of the man they’ll want to marry, and sisters grow up to be so pretty and have such nice nephews and nieces that it makes you proud to be an uncle. Sisters love you for many years after all other girls pass out of memory.

Brothers are the best boys in all the world. They can help you do so many things and they let you help them on some of the most interesting projects. In 1933 my little brother and I rode horseback 12 hours a day for a week and never had an unpleasant or unkind word. Brothers are good companions.

Everybody is an important as anybody to God. He loves them all. I’d like to be like that. If I could be a boy again I’d try to be tolerant and friendly to everyone. I’d speak only pleasant words that would make people feel good, especially those who seem to be less gifted, more homely, less popular, more bashful or more peculiar. Sometimes the most homely girls grow up to be the most beautiful mothers, or teachers, or neighbors and I’d sure like them to have fond memories of me.

I’d never make fun of a boy because he was different. Years ago in high school I knew a boy named Walter. Some of the class didn’t like Walter because they thought he was obnoxious in class. They called him “the perpetual interrogator” because he asked too many questions. Forty years later I met Walter. He had become a great man, highly respected, a real gentleman. I hope I wasn’t one who made fun of Walter.

Yep, it would be nice to be a boy again. I’d try to think about other people. Would what I’d say and do today bring happy memories fifty years away?

Payson, UT, 5 Feb 1985

Summer of 1936

I returned to Central at the end of my senior year at Tempe to thin cotton on the J.M. Smith farms. This I had done every spring for the past six or seven years as Father had worked for Smith and we lived in the old three-room shanty on the old Webb place. This was a great favor to me as it was the only work that paid $1.25 to $1.50 a day and was available during the summer to young men such as I. Father was home, working part time for Mr. Smith and part time for the WPA with my brother Earl who had recently married Velma. Mother and the younger brothers and sisters had gone to Heber, Navajo County, to help take care of Grandpa Porter who was in his last year of life. Cotton thinning would last about two weeks and after a week of seeking other work I would usually go to Heber for the balance of the summer where I had a standing offer to help my Uncle Alva Porter weed corn for my board and room, but this summer the college at Tempe offered a limited number of students the opportunity to come and work out their fall tuition on the college farm. This was about ten days’ work.

It was mid-morning in late June when I walked up to the highway in front of the Grand Central Market to hitch a ride to Tempe. Traffic was sparse and it took several hours to get a ride. During this time an altercation between a drunk “Oakie” and the store manager, Vaughn McBride, developed which ended in a fist fight and the sheriff appearing on the scene. Arguments and fights were very distressing and this cast a dark shadow of gloom over me for two or three days. By dark I had reached Ft. Thomas and then stood on the corner of the highway in front of the school house until mid-morning the next day before catching a ride on a truckload of potatoes going from Verden (New Mexico) to be peddled in Miami (Arizona). After an hour or two on the west edge of Miami I was picked up by a Mr. Brown, a car sales agent in Mesa. He was returning from Detroit with two new Chevrolet cars. After driving two or three miles he asked me to drive the car while he rode with his wife in the car behind. On the desert opposite Queen Creek he took one car and drove out to his farm and Mrs. Brown dropped me off in Mesa.

Feeling a need for clean clothes and having brought none with me, I caught a bus to Phoenix to try to get into a discount store before closing time. At the Tempe stop I saw my girl fried on the Mesa bound bus. Quickly I stepped off and walked to her window and asked permission to see her later that evening. Permission granted, I reboarded for Phoenix, made it in time to buy a pair of cotton slacks and a T-shirt for about $2.00. Returning to Mesa I walked out to Uncle Spencer Porter’s home (three miles east of town), cleaned up and returned to have a pleasant visit with Roberta.

I stayed with Uncle Spencer for a few days before the work started on the college farm. During this time he bought me a pair of tennis shoes to work in, for which I shoveled out his irrigation ditch -- about two days’ work. Uncle Spencer had lost an arm in World War I and could not use a shovel for heavy work. After finishing the work on the college farm I hitched a ride up to the Roosevelt Council Boy Scout Camp under the Tonto Rim, with Prof. Martin Mortensen, Jr. We worked at building a mess hall for the scout camp for a couple of days and then I started for Heber by walking up Christopher Creek to the rim road. Heber was about 25 or 30 miles from there and I had hopes of catching a ride on the rim road. A few miles down the road I came to a Forest Service lookout tower. The watchman was an old acquaintance, Burr Webb, who suggested that I stay overnight with him and as he was going into Heber the next evening for supplies I could ride in with him. In Heber I found that the folks had returned to Central two days before. I remained with Uncle Alva, hoeing weeds, until time to return to Tempe for my senior year.

The Skunk

(written in Payson, Utah probably 1982)

The skunk is a native American animal sometimes called a pole cat or a civet cat. They are about the size of the domestic cat but differ in many ways. They are larger in the hind quarters, and smaller in the front, and have a large bushy tail that is carried erect or arches over the back. They are always black and white. They are most often found in the semi-wild areas around farms. They eat almost anything -- small rodents, chickens, eggs, grub worms, garbage -- anything that tastes good.

Skunks have two main enemies: the horned owl who preys upon young, and the farmer’s boy who traps them for their pelts or traps them to protect the chicken flock.

Skunks are considered to be the reservoir of rabies -- a most dreaded disease. People get this disease when they are bitten by a rabid animal. When skunks become over abundant in an area, rabies in animals seems to increase.

The most peculiar thing about the skunk is his defense mechanism. It consists of two scent glands located at the base on the underside of his beautiful tail. He is able to spray scent from these glands very accurately and in every direction for several feet. He can even hit you in the eye when you are standing in front of him. And the scent is very, very strong and offensive and penetrates clothing and skin, and it takes many washings and many days to remove the smell.

My first encounter with a skunk occurred when I was seven years old. We were moving in a covered wagon from Central in Graham County to Heber in Navajo County in the spring of 1922. One night we camped on the edge of the Black River, and Father and I were sleeping on the ground between the wagon and the campfire. Mother and the two younger children were in the wagon. We were just starting to sleep when we heard the pans rattling by the dying fire. In the fading light, we saw a skunk eating the remains of the Dutch oven cake Mother had cooked for supper. I was excited and urged Father to get his rifle and shoot him. But Father calmly told me to be really quiet and watch but not move or disturb the skunk. After the skunk finished the cake, he ambled away, and we heard no more of him. Then Father explained that had we tried to kill him we would have caused a stinking mess in camp which would have spoiled the remainder of the trip.

It was a few years later -- when I was big enough to trap skunks -- that I learned the real value of his advice and found by experience how long the offensive smell of a skunk can stay with you to the dismay of your schoolmates, teachers, and family.

As so it is in life. When you listen to your father, you can avoid some awful stinking messes that may stay to plague you for a long time. (I have known some boys who refused to take their dad’s advice and who made mistakes that took years to overcome.)

Christmas, 1975

The Man with the Hoe

When Adam was driven out of the Garden of Eden, the Lord told him that the earth would bring forth thorns, thistles and noxious weeds to afflict and torment man and that by the sweat of his brow he would earn his living. Therefore, one of the first implements designed by man was the hoe which was essential to free his gardens and fields from weeds.

The shape and design of the hoe has not changed much in all the centuries of time. And until the development of chemical herbicides in the past two decades, the hoe was still used by man to protect his row crops from being run over by noxious weeds.

A boy in my generation grew up learning to use the hoe. One of his tasks at home was to hoe weeds out of the family garden and around the lot. One of his first jobs to earn money was to hoe weeds out of the cotton or corn fields.

Now hoeing weeds is a tedious task and requires a little skill and much energy and persistence. And after eight to ten hours in the field with a hoe you feel that you have done a good days work.

From the time I entered junior high school and until the time I finished college most of my summer employment was working with a hoe. As soon as school was out in the spring, we went into the cotton fields to thin the cotton with a hoe. Cotton was planted so that the plants would be about an inch apart. The job of thinning would usually last three to six weeks. Then if you were lucky, you could find occasional work hoeing the Johnson grass and weeds out of the cotton fields for another month or so.

In the cotton fields we used a heavy hoe nine to twelve inches wide. Often the hoe was made from an old shovel to give added weight and strength to stand the wear against the hard Gila valley soil. We always kept a water jug and file at one end of the field in the shade of a tree -- if one was available. The hoe would be sharpened at the end of each round, and we would get a drink of water and maybe rest a few minutes. The pay for a man and the older boys was $1.25 to $2.00. a day.

After the hoeing season was over on the Gila, I would go up to Heber in north central Arizona and work in the corn fields hoeing weeds for my granduncle, Alva Porter, who would give me a calf and my board for what usually amounted to one or two months work. In this way I was able to earn enough money to help with my education.

Boys don’t like hoeing weeds. It is hard work, and it is tedious and not the least bit exciting.

But grandpas love to hoe in the garden. It brings back pleasant memories of youth and gives them the opportunity to reflect on the lessons of life. A man’s character is like a garden. There are many weeds in the natural man that need to be hoed out before his character is beautiful. And boys who do not submit themselves to the weeding out process become like the garden that has not seen a hoe. All of the goodness and beauty is choked out by weeds.