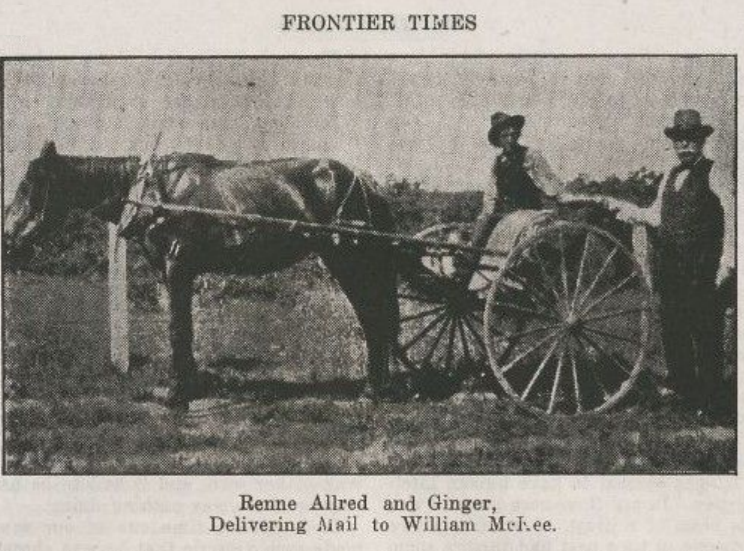

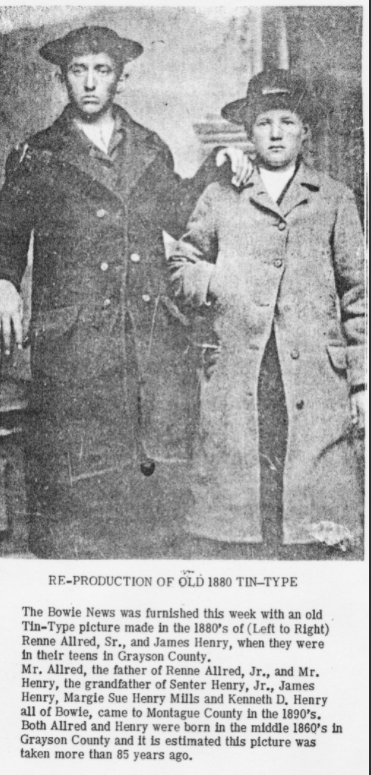

I was born December 2, 1864, in Grayson County, Texas, where my grandfather settled and fought Indians in 1837. In my youth I played town ball and bull pen with one J. H. Hurst. In after years Hurst went to Carlton College at Savoy, and he being a few years older than I, qualified as a teacher. I went to King and Gillespie, who founded a high school at Bells, Texas. Both schools were independently owned by the professors. Hurst taught one school at Cherry Mound, where he and I played together, and I challenged his whole school for a spelling bee. I had spelled down the Bells high school except Florence Scott, and tied her. We both missed the simple word of “separate.” I spelled it with an “e” and she spelled it with a double “r.”

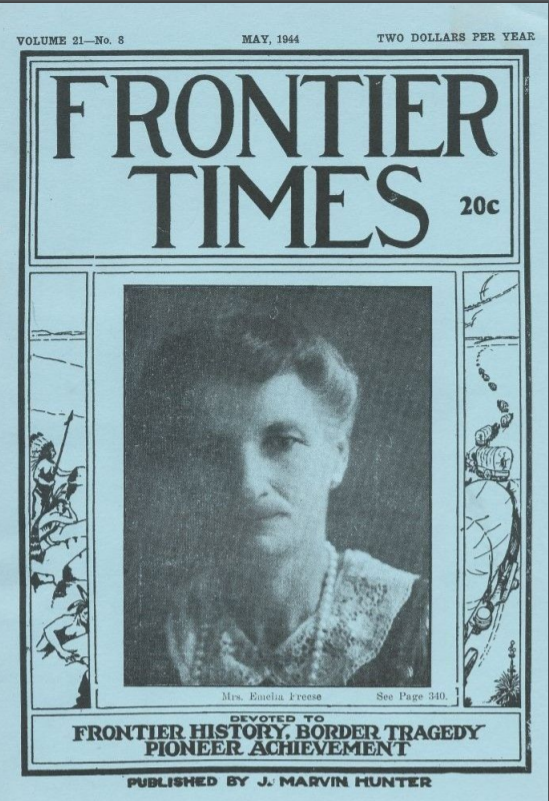

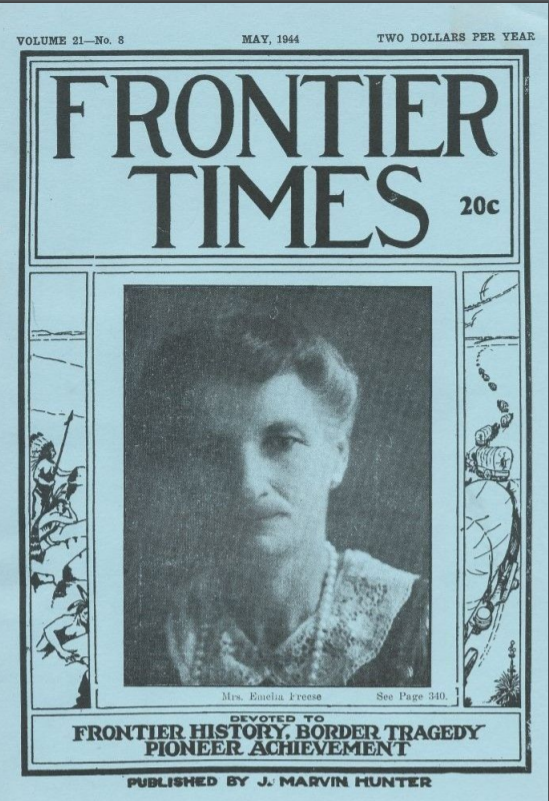

I was born December 2, 1864, in Grayson County, Texas, where my grandfather settled and fought Indians in 1837. In my youth I played town ball and bull pen with one J. H. Hurst. In after years Hurst went to Carlton College at Savoy, and he being a few years older than I, qualified as a teacher. I went to King and Gillespie, who founded a high school at Bells, Texas. Both schools were independently owned by the professors. Hurst taught one school at Cherry Mound, where he and I played together, and I challenged his whole school for a spelling bee. I had spelled down the Bells high school except Florence Scott, and tied her. We both missed the simple word of “separate.” I spelled it with an “e” and she spelled it with a double “r.”  So I went to W.C. Smith, the postmaster, and told him what I was contemplating. He said he had none, and By _____, I’ve got plenty of work without that,” and he wasn’t going to have it. I wrote Jim what the postmaster had said. His reply was that the postmaster had no more to say in the matter than he (Hurst) did, and to write to the Fourth Assistant Postmaster General for blanks. In the course of time I sent E.R. Wofford out for petition signers on Route 1, and I took Route 2, but the merchants found out what I was doing and told me to let up, that I would ruin the town, that people wouldn’t come to town to trade, and they would go broke. One of them talked to me in a very unfriendly manner on Mason Street. I tried to reason with him telling him that they had it all over the north, and why not bring it to our county; that we were entitled to it, and it would bring Federal money to our county. But, no, the old way of lining up at the post office on Saturday was good enough for them.

So I went to W.C. Smith, the postmaster, and told him what I was contemplating. He said he had none, and By _____, I’ve got plenty of work without that,” and he wasn’t going to have it. I wrote Jim what the postmaster had said. His reply was that the postmaster had no more to say in the matter than he (Hurst) did, and to write to the Fourth Assistant Postmaster General for blanks. In the course of time I sent E.R. Wofford out for petition signers on Route 1, and I took Route 2, but the merchants found out what I was doing and told me to let up, that I would ruin the town, that people wouldn’t come to town to trade, and they would go broke. One of them talked to me in a very unfriendly manner on Mason Street. I tried to reason with him telling him that they had it all over the north, and why not bring it to our county; that we were entitled to it, and it would bring Federal money to our county. But, no, the old way of lining up at the post office on Saturday was good enough for them. But I had to have two, and I decided C.R. Morgan, the junk dealer and feed man, could qualify. I went to him stating my predicament, and he said, “O.K.,” and signed; and so I congratulated myself on having two of his best men of my town sign my bond. But Charley’s wife had taught him to write and nobody except the bank could read his signature. In about three weeks the bond came back with a new blank, stating, “We cannot read the last name,” and to fill out the new one. I went to Giles with my trouble; thence to Charley, and I said, “They couldn’t make out your name. Take up this old bond and sign this new one, and do your best. It means a good job for me.” He signed again, and in about three weeks that bond came back with a letter, “You will have to get somebody who can write to sign your bond.”

But I had to have two, and I decided C.R. Morgan, the junk dealer and feed man, could qualify. I went to him stating my predicament, and he said, “O.K.,” and signed; and so I congratulated myself on having two of his best men of my town sign my bond. But Charley’s wife had taught him to write and nobody except the bank could read his signature. In about three weeks the bond came back with a new blank, stating, “We cannot read the last name,” and to fill out the new one. I went to Giles with my trouble; thence to Charley, and I said, “They couldn’t make out your name. Take up this old bond and sign this new one, and do your best. It means a good job for me.” He signed again, and in about three weeks that bond came back with a letter, “You will have to get somebody who can write to sign your bond.”