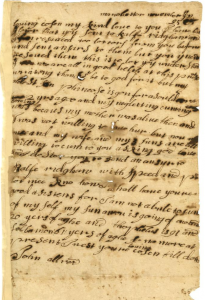

In 1695 John Allred wrote a letter to Phineas Pemberton asking for help to bring his family (his wife and three youngest sons Aron (also spelled Owen), Theophilus and Solomon) to Pennsylvania. John and his family were living in Manchester, England. Phineas was living in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. John wrote that although he had communicated earlier with Ralph Ridgway about coming to America, his mother had been sick and he had been unable to leave her. She had since died, so John was ready to leave England for America. This letter in the Pemberton Collection at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP) was a huge find and documented the Allreds were trying to come to America. Click Here to see that letter and read about its meaning to Allred History and Research.

In 1695 John Allred wrote a letter to Phineas Pemberton asking for help to bring his family (his wife and three youngest sons Aron (also spelled Owen), Theophilus and Solomon) to Pennsylvania. John and his family were living in Manchester, England. Phineas was living in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. John wrote that although he had communicated earlier with Ralph Ridgway about coming to America, his mother had been sick and he had been unable to leave her. She had since died, so John was ready to leave England for America. This letter in the Pemberton Collection at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP) was a huge find and documented the Allreds were trying to come to America. Click Here to see that letter and read about its meaning to Allred History and Research.

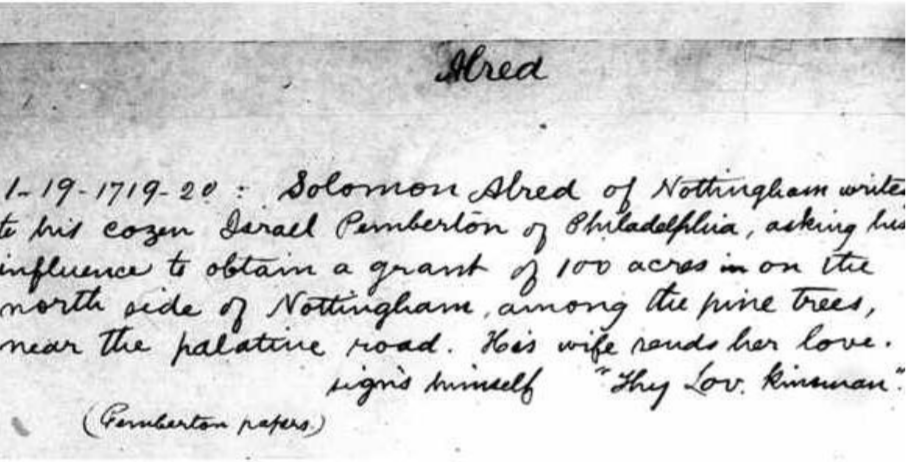

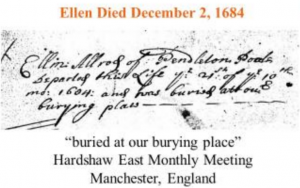

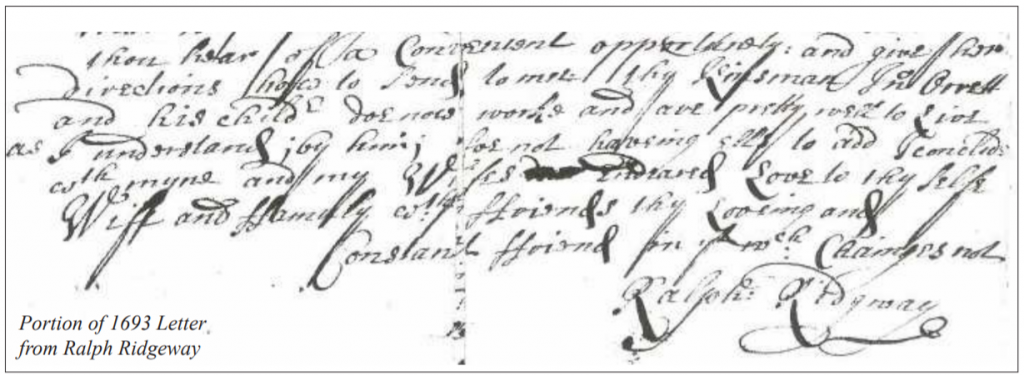

Phineas Pemberton Correspondence 1688-1691; #484A: On the “4th day, 8th month, 1693,” (October 4, 1693) Ralph Ridgway was at his home in Deansgate, Manchester, England. Ridgway was an active Quaker leader in Lancashire and personal friend of George Fox and William Penn. He was also the leader and founder of Hardshaw Monthly Meeting (MM), the first Quaker Meeting in Manchester. This was not a traditional church building as you and I are familiar with, but a congregation that took turns meeting in each other’s homes or out buildings. Many of the meetings took place in Ridgway’s home. Among the members of Hardshaw MM were John and Ellen Pemberton Allred. Ellen’s death in 1684 was recorded in East Hardshaw MM records and she was buried in their “burying ground” at Deansgate.

Phineas Pemberton Correspondence 1688-1691; #484A: On the “4th day, 8th month, 1693,” (October 4, 1693) Ralph Ridgway was at his home in Deansgate, Manchester, England. Ridgway was an active Quaker leader in Lancashire and personal friend of George Fox and William Penn. He was also the leader and founder of Hardshaw Monthly Meeting (MM), the first Quaker Meeting in Manchester. This was not a traditional church building as you and I are familiar with, but a congregation that took turns meeting in each other’s homes or out buildings. Many of the meetings took place in Ridgway’s home. Among the members of Hardshaw MM were John and Ellen Pemberton Allred. Ellen’s death in 1684 was recorded in East Hardshaw MM records and she was buried in their “burying ground” at Deansgate. Ridgway’s letter was full of news about various friends, some married, some gave birth, some dead. At the end of the letter, just before closing, he wrote “thy kinsman Jno Orrett [John Allred] and his children doe now worke and are pretty well to live as I understand by him….” This is wonderful news! Previous research had shown John Allred had struggled for many years to work and provide for his family. Documents found in Lancashire Court Records detail how each time he had found a place for his family to live and for himself to work, the neighbors/community ousted him because he was a Quaker. Religious persecution was fierce in 17th Century England! Ridgway’s letter brought welcome news that the family was finally doing well, working and thriving. Click Here to read more about John and Ellen's lives as Quakers in England.

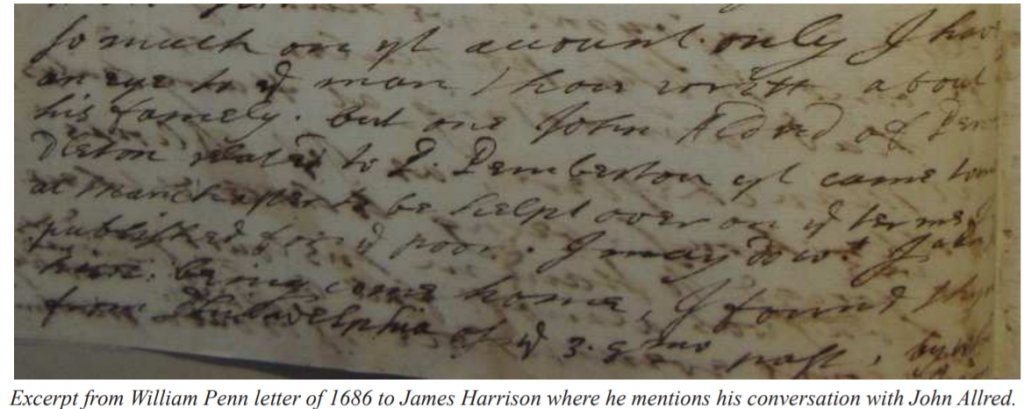

Ridgway’s letter was full of news about various friends, some married, some gave birth, some dead. At the end of the letter, just before closing, he wrote “thy kinsman Jno Orrett [John Allred] and his children doe now worke and are pretty well to live as I understand by him….” This is wonderful news! Previous research had shown John Allred had struggled for many years to work and provide for his family. Documents found in Lancashire Court Records detail how each time he had found a place for his family to live and for himself to work, the neighbors/community ousted him because he was a Quaker. Religious persecution was fierce in 17th Century England! Ridgway’s letter brought welcome news that the family was finally doing well, working and thriving. Click Here to read more about John and Ellen's lives as Quakers in England. Penn’s letter was filled with news of mutual friends and Penn’s travels throughout England as he continued to spread the message of the Quaker Doctrine. Toward the end of the second page, Penn wrote:

Penn’s letter was filled with news of mutual friends and Penn’s travels throughout England as he continued to spread the message of the Quaker Doctrine. Toward the end of the second page, Penn wrote: