Laban Allred and Family: Chickasaw Indians?

by Linda Allred Cooper

Laban was an Allred via two lines:

1. Laban, William, William, William, Solomon born 1680 Lancashire, England

2. Laban, Patience, Catherine, John, un-named daughter of Solomon and Samuel Finley, Solomon born 1680 Lancashire, England

It seems to be very popular these days to claim Native American ancestry. My own father insisted his grandmother or great grandmother or he isn’t really sure who she was but she WAS Indian. He swears there is a photo of her somewhere but he just can’t find it. I have traced the various branches of our tree and she just isn’t there. My dad's DNA results confirms he did not have any Native American ancestry. Sorry, Dad! Of course, his response is that I obviously have no idea what I’m doing or I would have found her. Every now and then we have that discussion all over again – with the same ending. Oh well…

It seems to be very popular these days to claim Native American ancestry. My own father insisted his grandmother or great grandmother or he isn’t really sure who she was but she WAS Indian. He swears there is a photo of her somewhere but he just can’t find it. I have traced the various branches of our tree and she just isn’t there. My dad's DNA results confirms he did not have any Native American ancestry. Sorry, Dad! Of course, his response is that I obviously have no idea what I’m doing or I would have found her. Every now and then we have that discussion all over again – with the same ending. Oh well…

Admittedly, an exotic ancestor with jet black hair and wonderful cheek bones or the promise of a check coming from the various Tribal Casinos is very intriguing – yep, I could find a use for that money! But, despite all the stories about the Cherokee Indian Princess who married into the family, there are very few records to document actual Allred claims to Native American ancestry.

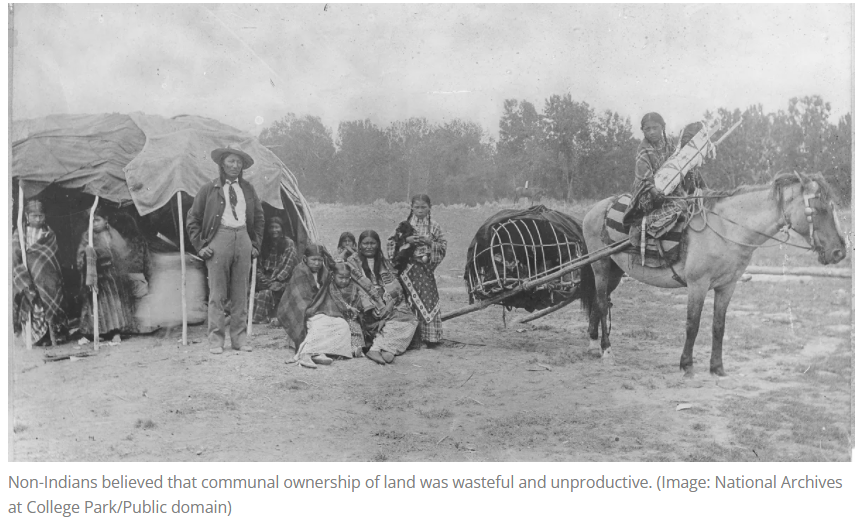

A great place to start Native American research is by referring to the Dawes Records. The Dawes Act was enacted on February 8, 1887. The Dawes Act had two primary purposes. The first was to “civilize” the Native peoples. Those sympathetic to the Indians, mainly philanthropists from the East, believed that the reservation system, in which most tribes held their lands communally, was preventing the economic and cultural development of the Native peoples. By the late nineteenth century most tribal economies were in dire straits, with indigenous people living in abject poverty. The Friends of the Indians, an influential group of philanthropists and reformers in the Northeast, believed that if individual Indians were given plots of land to farm, they would flourish and become integrated into the American economy and culture as middle-class farmers. In the Report of the Secretary of the Interior of 1886, Senator Dawes said he wanted the government to:

A great place to start Native American research is by referring to the Dawes Records. The Dawes Act was enacted on February 8, 1887. The Dawes Act had two primary purposes. The first was to “civilize” the Native peoples. Those sympathetic to the Indians, mainly philanthropists from the East, believed that the reservation system, in which most tribes held their lands communally, was preventing the economic and cultural development of the Native peoples. By the late nineteenth century most tribal economies were in dire straits, with indigenous people living in abject poverty. The Friends of the Indians, an influential group of philanthropists and reformers in the Northeast, believed that if individual Indians were given plots of land to farm, they would flourish and become integrated into the American economy and culture as middle-class farmers. In the Report of the Secretary of the Interior of 1886, Senator Dawes said he wanted the government to:

“put [the Indian] on his own land, furnish him with a little habitation, with a plow, and a rake, and show him how to go to work to use them .... The only way [to civilize the Indian] is to lead him out into the sunshine, and tell him what the sunshine is for, and what the rain comes for, and when to put his seed in the ground.”

“put [the Indian] on his own land, furnish him with a little habitation, with a plow, and a rake, and show him how to go to work to use them .... The only way [to civilize the Indian] is to lead him out into the sunshine, and tell him what the sunshine is for, and what the rain comes for, and when to put his seed in the ground.”

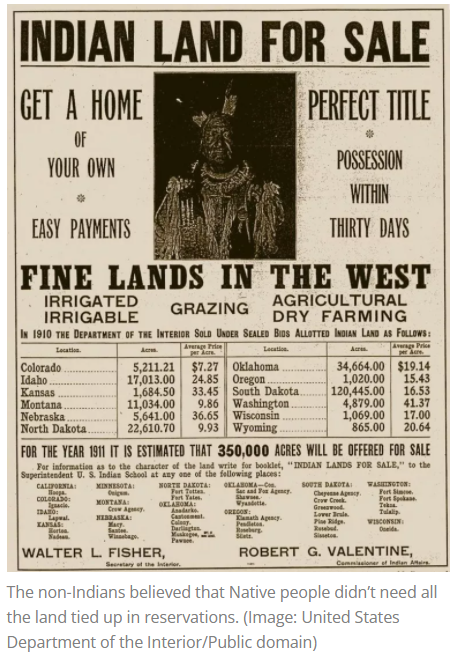

The second major purpose of the Dawes Act was to gain use of Native-American lands for non-Natives. The act called for breaking up large tribal landholdings to enable settlement of the West by non-Natives. The act secured only a part of the tribes’ lands for the Indians, opening the remainder to settlers. An Act passed August 9, 1888, regulated the marriages between white men and Indian women and their rights to the land. White men were prohibited from marrying Indian women. If a white man did marry an Indian woman, he would not be entitled to any of her property. However, white men did marry Indian women and most were looked down on by both races. There is a report from one Indian Agent who stated:

“They as a rule marry the squaws for the advantages and opportunities such a relation affords and proceed to make the most of the situation. They gobble up what the Indians make, advise them to their hurt generally against Government Agencies, deal liquor to them and debauch their morals…”

One Indian Relations annual report included the following comments about a particular “well to do white man…married to a member of the owned land. This act was intended

“to prevent a self-seeking white man from marrying an Indian woman for the purpose of raising a brood of mixed-blood children, living on the reservation with their tribe, enjoying the product of their land and drawing annuities in their name.”

In the midst of all of this controversy, we find the Laban Allred family living in Carroll County, Arkansas, who in 1896, were filing applications with the Dawes Commission to be recognized as members of the Chickasaw Nation. The question is Why?

Laban Allred (1813-1903) was born in Randolph County, the son of William Allred (1765-1849) and wife Patience Julian (1772-1856). He left home as a young man and per the 1840 Federal Census, Laban was living alone in Upper Osage, Carroll County, Arkansas. Per the 1850 Federal Census, Laban (38) had married and he and wife Sarah (20) were living in Osage Township, Carroll County, Arkansas with children Sarah Ann (5), William (3) and Polly J. (2 months). Laban listed himself as born in North Carolina, wife Sarah born in Tennessee and all three children born in Arkansas. In the “race” column, all are listed as White.

Per the 1860 Federal Census, the family is still living in Osage, Carroll County, Arkansas. Listed are Laban (47), wife Sarah (31), Sarah Ann (12), William (11), Patience J. (10), James M. (8), Caledonia (5), Amanda C. (4) and Alfred (2). Once again, in the race column all are listed as white and Sarah was listed being born in Tennessee. Per the 1870 Federal Census, the growing family was living in Liberty Township, Carroll County, Arkansas. Laban (58), wife Sarah (41), Sarah Ann (22), Patrice J. (20), James M. (18), Caledonia (15), Amanda (13), Alfred (12), Alson G. (9), Davis (7), Laban (4) and Robert Lee (2) and all are listed as white again. Sarah was listed being born in Tennessee.

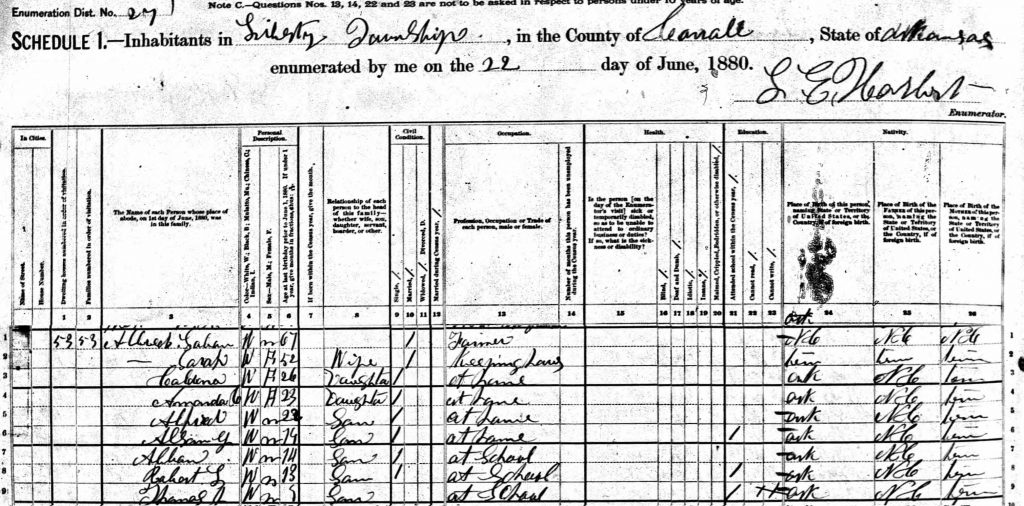

Per the 1880 Federal Census, the family was still living in Liberty, Carroll County, Arkansas. Laban (67), Sarah (52), Caledonia (26), Amanda (23), Alfred (22), Alson (19), Albin (14), Robert Lee (13) and Thomas J. (9). All listed as white and Sarah as being born in Tennessee along with her mother and father.