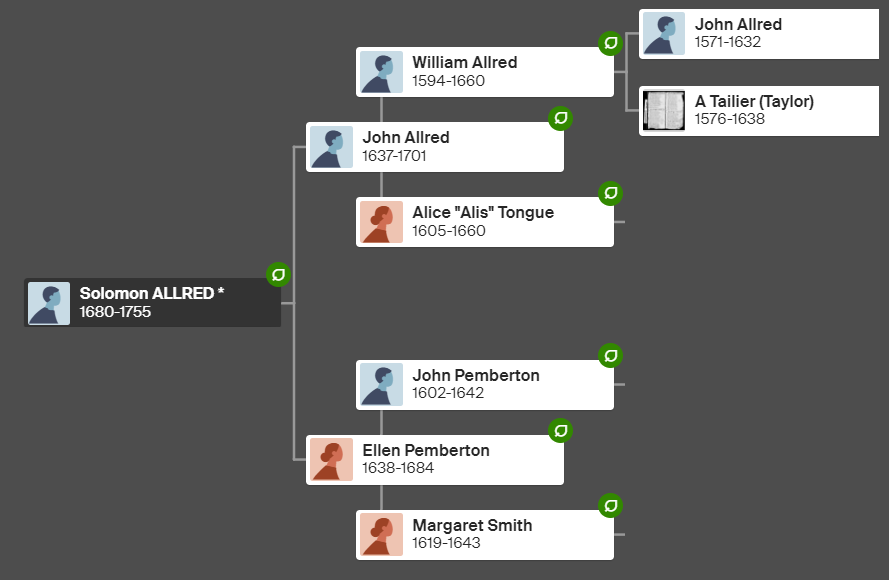

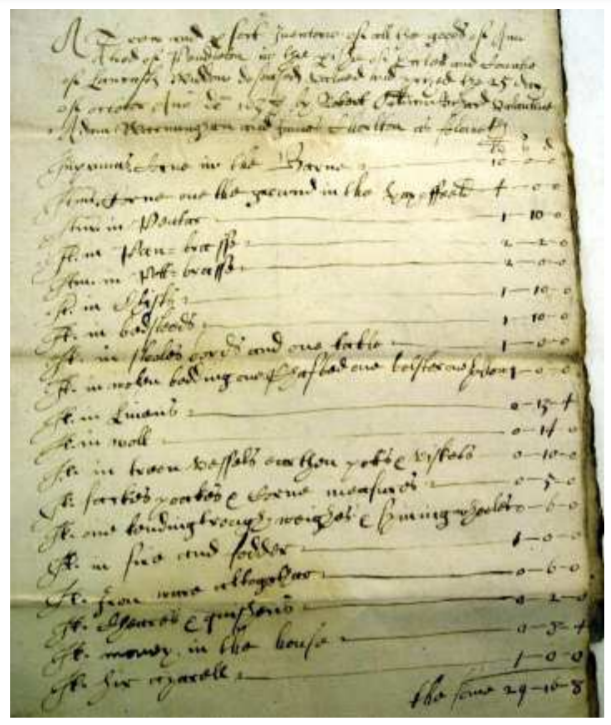

Ann Taylor/Tailer 1576-1638 was the Great Grandmother of Solomon Allred born 1680 Lancashire, England. Ann and her husband, John Allred 1571-1632 were the Grandparents of Solomon's father, John Allred 1637-1701, who married Ellen Pemberton 1638-1684.

Transcribed by Dr. Leslie Lockett of Ohio State University:

In the name of god Amen, the 13 day of December in the yeare

of our Lord god 1637 Ann Alred of Pendlton in the parish of Eccles

and Countie of Lancaster Widdow beeing infirm and aged yet

in good and perfect memorie doe institut ordaine and make this my

Last will and testement in maner and form as foloweth ffirst

and principall I comit my sowle into the hands of god my creator

trusting to be saved by the merits of Jesus Christ my saviour

and my body to Christian buriall in the parish church yard of

Eccles and as for my worldly goods which god hath blessed me

with all in manar and form as foloweth. Aftar my

debts bee payd I give to my daughtar Ann Travis one shilling and

also to my daughtar Elizabeth Bradshaw one shilling and

also to my daughter Cataran Ouldam one shillinge and as

for all the rest of my goods I give them wholly to my

Soone William Alred to be at his disposing for the good of

My Sonn John Alred and to be given him at such

tim as he in his discretion shall thinke fitt and also I ordaine

and make my Sonne William sole executor of this my

last will trusting that he will see the same performed as and

acording to the trew intent and meaning of this my Last

will and to this my Last will I have sett my hand and seale

the day and yeare above said

Witneses here of Ann Alred

hir marke

Isach Taylor

his marke

/s/ James Chorton [Chorlton]

Transcribed by Dr. Leslie Lockett of Ohio State University:

Ann Allred of Pendleton: Her Will (1637) and Her Probate Inventory Record (1638)

by John Allred of Dublin, Ohio

John's Lineage: John, Cleveland R., William R., Coleman S., Samuel, Elias, Thomas, Solomon born 1680 Lancashire, England

This research report was originally posted in the Allred Family Newsletter #86, Spring 2011

Will and Inventory transcribed by Dr. Leslie Lockett(1) of Ohio State University.

Cameras were not available in the 17th Century so we do not have a picture of Ann Allred of Pendleton. But, thanks to the British penchant for record keeping, we have a snapshot of her life. Her will and probate inventory record were among hundreds of thousands of items housed in the Record’s Office in Preston, Lancashire, England. Visitors to the Records Office will find a treasure of historical documents. All that is necessary is to sign in and obtain a Reader’s Ticket and begin the search.

Our search quickly turned up a book listing wills from 1637. The index of that book showed the name “Ann Alred of Pendleton.” Since it has been well established that John Allred, the father of the first immigrant to America, Solomon Allred, was from Pendleton, Eccles Parish, Lancashire, it seemed likely that she must be in our ancestral line.

A cursory examination of the will confirmed that this particular Ann Allred was the ancestor of Solomon. A cursory reading was all that was possible, however. Even though the will was written in Early Modern English, a cursive script was used which, for the most part, is unrecognizable to the untrained eye today. The original will, which was written on a rather thick paper, much like blotter paper, was photographed in the Preston Library.

The will, written on December 13, 1637, gives us a lot of information. It tells us that Ann “Alred” (Allred) was a widow from the small village of Pendleton in the Parish of Eccles (rhymes with “heckles”) in the County of Lancaster or, as the English say, Lancashire. We know from other information(2) that Ann Taylor (Tailor) was born about 1572 and that she and John Allred of Pendleton were married at the Parish Church, Eccles, Lancashire on May 27, 1589. While there has been some confusion as to the spelling of Ann’s maiden name (Taylor or Tailor), it is interesting that one of the witnesses to the will was Isach Taylor who was probably a relative of Ann’s, perhaps her brother. This would suggest that the correct spelling is Taylor but Isach Taylor, like Ann, was unable to write his name and signed with his mark.

The will makes clear also, at the time of it’s writing, she was a widow with five living children: three girls and two boys. The girls were all married. The first mentioned and the oldest daughter, Ann (b. 1596), was married to John

Travis (Trauis) on February 19, 1621 in Saint Mary the Virgin Church, Eccles Parish. A second daughter, Elizabeth (b. January 13, 1604), was married to Adam Bradshaw on May 19, 1632. The third daughter whose name appears to be

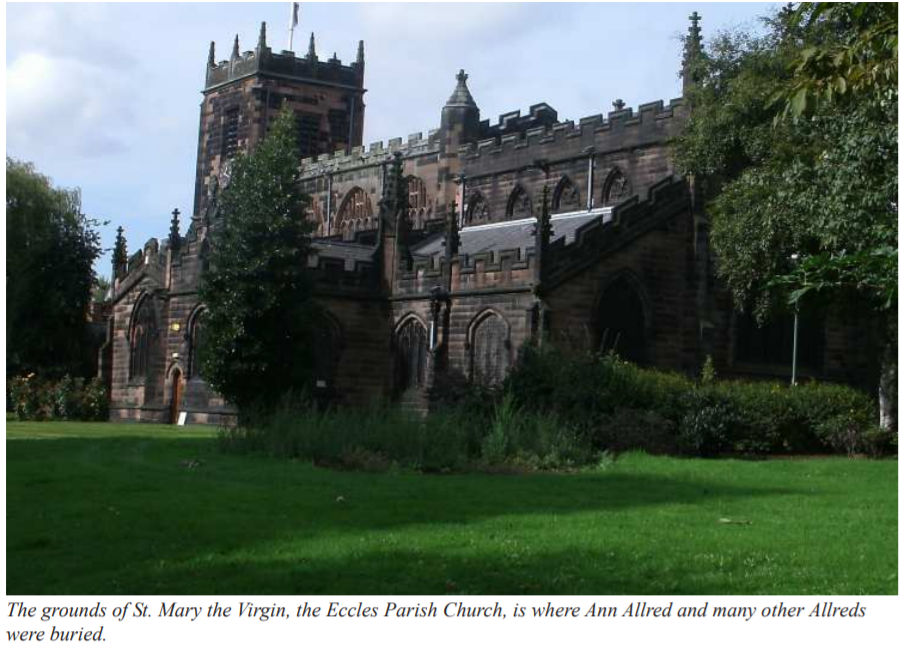

Cataran Ouldam was actually named Catherine (b. August 29, 1602) which was badly misspelled by the scribe. The Eccles Parish Church records show that a Katheryne Ouldam was buried in the church yard on January 15, 1647. Unfortunately, as noted above, any mistakes on spelling of names could probably not be corrected by Ann Allred, as evidenced by her signing the document using “her mark.” The girls were each given one shilling.

The sons are named William and John. In fact, William may have felt he had been surrounded by men named John Allred for his whole life. His grandfather and his father were both named John Allred and his younger brother was also named John.

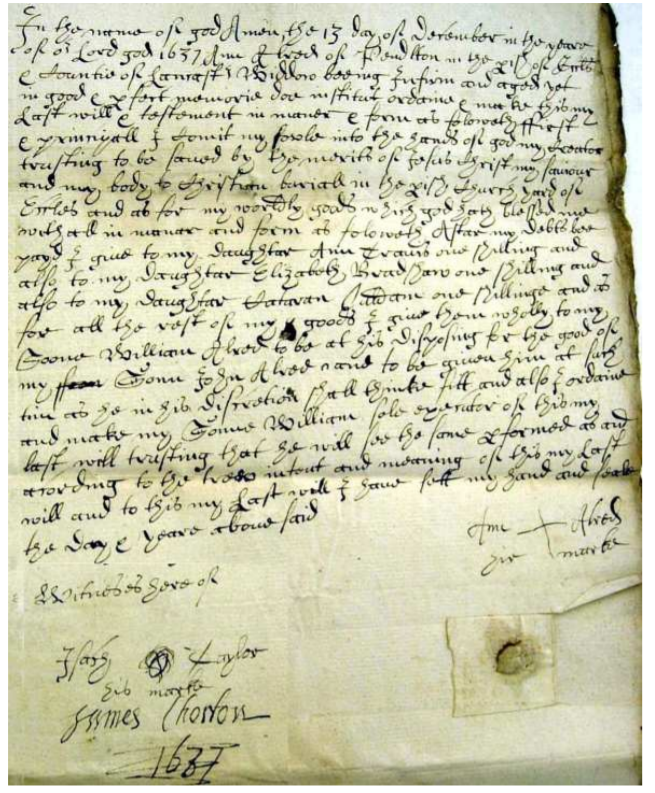

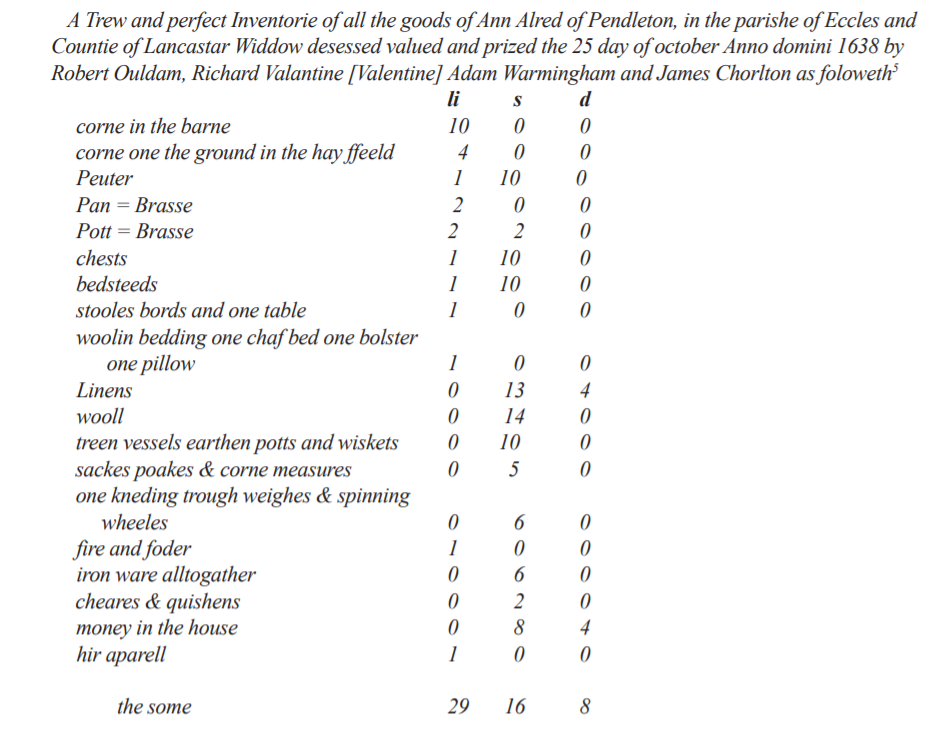

As was customary at the time, William b. September 29, 1594(3), being the oldest son, was given all of Ann Allred’s worldly goods with the exception of the three shillings left to the three girls. Ann admonished William to share with his brother John (b. Jan 10, 1607) “in his discretion as he thinks fit.” There is no record available to let us know how much he shared. We do have a record of the property that William inherited. An accounting was made, dated October 25, 1638 (only three days after Ann Allred’s burial) and submitted at probate with another copy(4) of the original will.

The value of her personal possessions is recorded in pounds (li), shillings (s) and pence (d). Note that there are 20 shillings per pound and 12 pence per shilling. In today’s money, using the price index, the value of her property would be about 3,200 pounds or about $4,800. She wasn’t rich. The most expensive item in her personal property was “corn” “in the barne (barn)” and “one (on) the ground in the hay field,” worth a total of 14 pounds or about half of the value of her worldly goods. The word “corn” didn’t mean what it means today. In fact, at the time of the will, corn as we know it probably was not grown at all in England but rather corn was a “new” grain introduced to the Pilgrims by the Native Americans in Massachusetts after the Pilgrim’s arrival in 1620. To the English, the word “corn” was used to describe any grain(6) dating back to the 10th century so when the pilgrims said “Indian corn” they were actually saying “Indian grain.”

The “corn” listed in Ann’s will was most likely wheat or barley. Ann Allred’s brass pots and pans were obviously prized possessions. They were worth considerably more than all of her “iron ware” which was undoubtedly used for cooking over an open fire, most likely in the middle of the room.(7) To aid in cooking and serving, she had “treen”, i.e. wooden(8) and “earthen vessels,” valued at 10 shillings. She had a “kneding trough” which was used to knead bread dough(9) and a spinning wheel for making thread from which cloth was produced. She must have done that well because “hir (her) apparel” was valued at one pound!

Another indicator of how they lived was the item listed in the inventory as a “chaf bed” which was a mattress cover filled with straw (chaff) to make a straw bed. It is not clear what “fire and fodder” means unless it is wood for cooking and heating fires and fodder to feed animals. Most of the other items - chests, stools, table, linens and wool - would have been familiar possessions in the American frontier well into the nineteenth century. Cheares (chairs) and quishens (cushions) would have also been familiar except for the spelling.

It is apparent from the list of personal property, Ann Allred’s family were poor farmers as most people were at the time. In 17th century England, a farmer who owned his land was called a yeoman and was such a rarity that the man was identified by the word “yeoman” attached to church burial, marriage or parenting records and to legal documents. Neither Ann’s husband’s (John Allred) burial record, dated March 20, 1632, nor his probate inventory record, dated10 March 26, 1633, describe him as a yeoman. It is therefore safe to assume that the family was tenant farmers, sometimes called “cottagers” because they lived in cottages on the land owner’s property.

Ann was obviously a very devout Christian who wanted to “commit my sowle (soul) into the hands of God” and stated her desire to be buried in the Eccles Parish Church yard. The Parish church was and still is Saint Mary the Virgin Church located on Church Street in what is now the city of Salford (although the Parish has many other churches now). She got her wish. Her burial was noted in the Eccles Parish Church records as simply: Ann Allred, widow, October 23, 1638.

Our story might appropriately end at this point but there is more which connects us and our heritage to Ann Allred. The man who presided over Ann Allred’s funeral was John Jones, D.D., who served as vicar(11) of the Eccles Parish

Church from 1610 to 1659 during perhaps the most tumultuous time in British history. Although John Jones contributed money to King Charles I when it was asked of the clergy, he was a Puritan. Recall that it was the Puritans, led by Oliver Cromwell, who took over the country from 1642 to 1659. John Jones, as early as 1622, was reported to ignore Church of England procedures(12) when he “gave communion to those who sat; and though nobody stood at the creed or bowed at the name of Jesus, no presentments were made,” meaning that he did not report any misbehavior of the congregation. It is not surprising then that he embraced Presbyterianism when it was established as the official church in England by the Puritans. The upheaval in governance ended in 1659 returning the Church of England to its prior status under the monarchy.

That also ended the tenure of John Jones, Puritan, as vicar of the Eccles Parish Church. While it is uncertain why John Jones left his office as vicar, it is known that his son, Edmund Jones, replaced him. Edmund Jones did not last long in that position – he was ejected from the Church in 1662 for “non-conformity.” That term was used to describe clergy who refused to comply with the Act of Uniformity passed by Parliament on August 24, 1662 after the restoration of Charles II as King(13). The act required clergy to consent to the entire contents of the Book of Common Prayer which was the order of worship demanded by the Church of England. Edmund chose not to continue his ministry in the Church of England but rather to join the Presbyterians, following in his father’s footsteps. This is the same Edmund Jones who led an illegal Presbyterian meeting on October 12, 1673 which listed a John Allred as a participant, along with 45 other members of Reverend Edmund Jones’ Presbyterian congregation.(14) This Presbyterian John Allred was related to Ann Allred but it is not clear which John Allred he was. That is, he could have been Ann’s son or grandson: the will shows that Ann had a son named John and we know that she had one and perhaps two grandsons named John.(15) Thus there are numerous suspects named John Allred, but at this point it seems unlikely that the Presbyterian John Allred was our ancestor, the father of Solomon. That John, the husband of Ellen Pemberton Allred, was arrested over a decade earlier on June 16, 1661 for attending a Quaker meeting(16). The same source shows that Ellen Allred had been arrested for attending a Quaker meeting the previous year on February 10, 1660. We also know that Ellen Pemberton Allred died a Quaker(17) on December 21, 1684, and that on January 16, 1686, William Penn told James Harrison in a letter(18) that he was considering helping John Allred of Pendleton to come to America as an indentured servant, which strongly implies that John Allred was still considered a Quaker.

Thus, the evidence of John (and Ellen)