Mary & Clement Allred 1932

Clement ALLRED

Allred Lineage: Clement, Ephraim Lafayette, Reuben Warren, James, William, Thomas, Solomon born 1680 England

Born: 06/07/1903 Ferron, Emery Co., UT

Died: 07/09/1978 Lawndale, Los Angeles Co., CA

Submitted by: Don Allred 02/10/2001

This chapter is the second part of the oral history of Clement Allred, recorded on tape January 1974. The tapes were transcribe by Dawnell Griffin in January of 1987.

Montie and I moved from the original place where we lived, to a large boarding house for boys, closer to the university. We got a job in the boiler room at the school working four hours a day to help pay our board and room, but it wasn't enough. We worked there, anyway, expecting everyday to receive money from the horses we had sold, so that we could continue our school.

Finally we got in a spot and didn't have enough money to pay our board. We didn't know what to do. It was very embarrassing. We expected money every day, but nothing happened. We had just gone through the experience of losing our father. We had taken him to Ferron and buried him there with Mother in the same plot with some of his children. We were very unhappy and under a strain, not

Finally we got in a spot and didn't have enough money to pay our board. We didn't know what to do. It was very embarrassing. We expected money every day, but nothing happened. We had just gone through the experience of losing our father. We had taken him to Ferron and buried him there with Mother in the same plot with some of his children. We were very unhappy and under a strain, not

having any money. We felt that the landlady thought we were just trying to get by without paying.

"What should we do? Should we quit school?" We didn't want to quit; we wanted to get an education.

I said, "I'll tell you what let's do. Let's go to the bank here in Provo and borrow the money until our money from the horses comes."

Mont said, "You talk like a crazy man. How can we expect to get a loan without security?"

I said, "We can tell them that we have money from the horses coming."

He said, "O.K." We went to a bank in Provo. Of course, we were strangers (just a couple of kids). We didn't know anybody, but we had a lot of nerve. We asked for the manager. We went into his office and told him we were expecting money for these horses. We were going to the BYU and wanted to get a little loan until the money came through.

He looked at us like, "Well, at least these boys have a lot of nerve." He told us in a very friendly way, "It isn't customary for us to let money out without security. You don't have security?"

We said, "No, we don't have."

He said, "I'm sorry, but we just don't do that." Finally he said, "What was your father's name?"

"Ephraim L. Allred."

A kind of smile came over his face. He said, "Well, listen boys, I didn't know your father too well, but I know of him through his reputation. If you are the sons of Ephraim Allred, I'll let you have the money. In fact, I'll sign the note myself."

We were only asking for $150, but at that time, it was a lot of money. He called in a girl and had her bring a note. He signed it and we walked out with the money. I'll tell you, folks, I was ten foot tall. What a wonderful thing it is to have a good name. My father was known as "Honest Ephraim Allred."

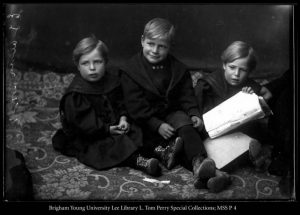

(photo: brothers Clement, Justin and Clemont) We were identical twins. We looked so much alike, people couldn't tell us apart, unless we were face to face or right together. I had a mole on my left cheek. That was about the only way you could tell who was who, and then only if you looked real close. We had a very, very funny experience. Montie met a girl and they became quite attached to each other. She didn't know he had a twin brother. Montie would come and tell me about her.

(photo: brothers Clement, Justin and Clemont) We were identical twins. We looked so much alike, people couldn't tell us apart, unless we were face to face or right together. I had a mole on my left cheek. That was about the only way you could tell who was who, and then only if you looked real close. We had a very, very funny experience. Montie met a girl and they became quite attached to each other. She didn't know he had a twin brother. Montie would come and tell me about her.

He'd say, "You know, I met a girl the other day that..." Boy, he just raved about her! He really fell for her. One day I happened to go into the post office and a girl came up to me. She seemed to know me, but I didn't know her, so I just ignored her. You couldn't blame me. She had a girlfriend with her, and apparently she'd been telling her about the boy she'd met and how they were very attached to each other. When I came in and ignored her, it was must have been very embarrassing. A short time later we went to a dance.

Montie said, "I hope I see this girl. I sure want to see her again."

Sure enough, here she came. The first thing Montie did was walk up and ask her for a dance. She turned him down cold. He just couldn't understand how things could change so quickly. A little later they met and started talking. She jumped all over him and bawled him out about how he'd ignored her in the post office.

Montie said, "I've never met you at the post office but I've got a twin brother. I bet ya I know what's happened—my twin brother." He got us together and explained to her.

"Well," she said, "I'll never make that mistake again."

I said, "I'll bet you before the year's out that I'll take you home and you won't know the difference."

She said, "I'll take that bet." Knowing about the mole on my cheek, she said, "I have a way of telling, and I know you can't pull that."

A few months later, Montie went to a Lyceum course and he took her. A lyceum course is a traveling course or group that travels from college to college with unusual things, entertainment and that sort of thing. I was out with the boys when Montie took this girl to the lyceum.

Montie and I dressed quite a bit alike, but our overcoats were different, and when it was cold we wore overcoats. We were coming home from the movie when we passed the place where Montie and this girl were.

I said, "Listen. I've got a little bet with this girl that I can take her home and she'll think it's Montie. You tell

Montie, when he comes out with her, that he's wanted around the corner here." (I went around the corner of the building in the hallway.) When they came out, one of the fellows said, "Your brother wants to talk to you a minute." Montie excused himself, left her, and came around to where I was.

I said, "Change overcoats with me [because our overcoats were different] and let me put your overcoat on." I turned the collar up so she couldn't tell it was me, and then I said, "I'll take her home and you follow along behind. This will just be a little joke."

He said, o.k., so I put his overcoat on and turned the collar up. I came walking up to her and said, "Let's go." She took a hold of my arm and away we went. Montie and my friends were about a half a block behind, having a lot of fun. I took her on home, but when I got her to the porch or to the place where she lived, she started talking about something that had happened between the two of them that I didn't know a thing about. I couldn't answer an intelligent question. She asked me a question I couldn't answer, because I didn't know. All at once she reached up and felt the mole on my cheek (that mole has been gone for many, many years). Montie and the boys came up and had a real good laugh because she hadn't known the difference until she felt my mole.

Montie and I finished that year at school. When spring came and school let out, we went to Carbon Co. and worked on the state highway. We had a lovely experience working there, due to the fact that our father had been the road supervisor at one time. We figured that would be a good place to get a job. The first summer after going to BYU we worked all summer in Carbon Co. around Price, Utah, and Indian Canyon and through there. We made enough money to go to school the next year, and we came back the same as before. In the meantime, Arvil and his family left the farm in Vernon and moved to Provo. That made it real nice for Montie and me, because we could live with them in Provo. How wonderful it was. Ernest was out with the sheep a lot during that winter, so Harriet was in Provo too.

We lived with Alta and Arvil and their family. What a joy it was to be with them and their children, Jay and Marjorie, Ethella and little Maxine. What a lovely, wonderful time we had there that winter.

The next spring, Mont and I decided we would go out and sell woolen goods for the Utah Woolen Mills in the summer-time so we could go to school in the winter. We bought a little Model T Ford. The seat came down so we could make a bed out of it. We went into Colorado and had a wonderful summer. We went to Grand Junction and all through there. It was great to be out with Mont, and we were quite successful. We had about a thousand dollars worth of samples and big suitcases that we carried the samples in. We showed the samples and sent in the orders and they'd send out the product. Utah Woolen Mills was very popular because of the cold winters. They had woolen underwear, blankets, and many different beautiful sweaters. They had one particular bright, shiny, red sweater that was just beautiful. It would catch your eye. Nearly every woman who saw it wanted one, but they'd say, "Well now, have you sold many of these around this area?" They didn't like to wear the same thing.

Mont would say, "We haven't sold any around here, but we've only been in town a short time." So we'd take the order for it.

A couple of weeks later we were in Ludville, Colorado staying at the hotel. We ran across a couple of Utah Woolen Mill salesmen, in fact, students from the BYU, just like Mont and I.

"So," they said, "you boys came through Grand Junction." We said, "Yes". They said, "We already knew that. All you can see there are shiny red sweaters." I don't know whether Montie and I'd dare go back there or not because we sold so many of those.

Montie and I didn't go back to the BYU. We stayed quite a while in Price and sold Ford automobiles for John Red Fords. We'd go into the mining camps --Standardville, Castle Gate, and Hiawatha. We'd go to Sunnyside, and we had a wonderful time in Price.

Arvil, by now, had it real nice in Provo. Columbia Steel was coming to Provo. They sent people out looking for silica sand to mix with the ore. Utah has quite a lot of silica. Arvil's cousin was a geologist and had known Arvil at Utah State Agricultural College. When they heard that Columbia Steel was coming to Provo, they went out prospecting and found this silica sand in the Price Canyon. Just above Springville, the whole mountain was silica sand. They could blast it, mine and load it in cars, and take it to Columbia Steel. That was what they wanted. They came to Arvil and his cousin and asked them where to find the silica and what they owed them for this information.

The geologist said, "You give Arvil Olson here a good job. That's all we have to have."

So they gave Arvil the job of getting this sand out. Arvil was pretty smart. He worked for a while with a crew of men, but he finally decided to take a contract, do his own hiring, and go it by himself. He was very successful in this. He was clearing about a thousand dollars a month. He bought property in Provo and was very successful. Then he had a little bad luck. He didn't have insurance. He had hired a fellow who was blasting out the side of the mountain quite close to the road. He put an overload of dynamite and blasted. Some of the rocks came down on the highway and one hit a car. Arvil was sued for everything he had, except the home he was living in.

Mont and I went up to Costella Springs and worked with Arvil for a while. Then we spent a little time a thousand feet below the surface at the Park City Mine. We worked in the mine for two or three months but we didn't like the mine at all.

We decided to go on into Salt Lake City. We sold Ford cars for the Baker Company. Then we met a fellow by the name of Kirkpatrick, who wanted us to go into the insurance business for the Equitable United States in its Salt Lake office. He convinced us to sell at the Equitable. He was district manager, and hired Mont and I. We went to Bingham, Utah, and spent two and a half years selling insurance.

While we were in Bingham, we met a very good friend who was with us many years. His name was Eddy Carlos. He worked in the mines in Bingham and we sold insurance. Another good friend who we met there was Charles Harold. Later he came to California.

Then we went back to Salt Lake. We quit the insurance business, and like young fellows do, we jumped around quite bit. I wished that we'd stayed in the insurance business, but we decided we wanted to come to Salt Lake. I got a job in Sears Roebuck in the shoe department selling shoes. Mont got a job at the Goodyear Tire and Rubber. One day Eddy Carlos came to Salt Lake and told Mont and I that he was going to California. That was in 1929. His folks were quite well to do and had bought him a new car, a new Chevrolet Coupe.

"I'm going down to California and I'd like to have you boys go with me if you would," he said. "It won't cost you anything to go down. I've got this new car."

Montie knew that he could transfer from Salt Lake with the Goodyear Tire and Rubber. They'd already talked to him about it and said they could get him a job down there. Mont and Eddy were going to California, but I didn't want to quit my job. I had a good job in the shoe department and I liked it.

They came to me and said, "Won't you go with us?"

I said, "I hate to quit my job." Still, I just couldn't conceive of Montie leaving and us splitting up. When Mont and Eddy were about ready to go, I said, "You come by and I'll make a decision whether I'll stay or whether I'll go. You come by." (They were going to leave the next day.)

It was April or May, in the spring of the year. It was cold, and the winter wasn't over yet in Salt Lake. I went to work that morning. Mont and Eddy were going to leave at noon for California. Finally I said to myself, "I'm going to quit my job and I'm going to go with them." I thought, "I'll go on the trip, anyway, and probably come back with Eddy." (He wasn't going to stay.) I went to the manager and asked him if I could have a leave of absence.

He said, "What do you want a leave of absence for?"

I said, "Well, I have a chance to go on a trip to California."

"Who wouldn't like to go?" he said. "I can't give you a leave of absence until you get your vacation."

"Well," I said, "how soon can you get my money ready then because I'm quitting."

"Do you mean you'd quit?"

I said, "I do. Just as soon as I can get my money, I'm quitting."

He went ahead and got my money for me, and at noon, Mont and Eddy came by in his Chevy coup. We went up to the place where we were boarding, loaded our things, and away we came to California. It was a brand new Chevrolet car, and we had a lark. Eddy was a real pal.

We left Salt Lake and decided to drive right through and see how soon we could get to Los Angeles. They didn't have the roads they have now. I remember there were graded roads and graveled roads most of the way. One of us would drive for two hours. We had an alarm clock in the coup, and when the alarm clock rang, we changed drivers. Then we would go right on for another two hours. The only time we'd stop was to eat a little bit. It took us 18 hours, and at that time we thought it was a real record.

We really fell in love with California and the beautiful sunshine. We decided we'd try and stay. Mont went to Goodyear Tire and got a job. They gave him a transfer, and Eddy and I decided we'd go to Standard Oil in El Segundo to see if we could get on there. They gave us both a job, but we had to pass physical examinations. Eddy passed with flying colors, but after they examined me, they found I had a potential hernia. If I did any heavy lifting, I could be ruptured and they didn't want that. I was turned down, and Eddy got his job.

I didn't know what to do. I didn't have a job, and I didn't have much money with me. I thought, "The only thing I can do, I suppose, is go on home." We had a couple of real good friends, Albert Foote and Dennis Soderquist (from Ferron), who had come down in 1924 and joined the Los Angeles police force. Dennis lived across the street from us. Both of those boys were on the Los Angeles police force.

Finally, I had about five dollars left to my name and my fare home. I went down to say goodbye to Dennis Soderquist. I felt very, very sad. I was leaving Montie and Eddy, but I had to go. I told Dennis I was going home. He said, "Why don’t you stay here and find a job?"

I said, "I'd like to, but I'm running short of money. I've looked several places, and I haven't found a job."

"Well," he said, "if you need money, I can let you have it." He handed me a 50 dollar bill. "If you need more, you just come and see me." I decided I'd stay. I looked up Albert Foote (being a policeman and all), who suggested I go to the Union Pacific Railroad. He said I could get a job as a special agent, working in the railroad yard and checking the seals on the freight cars.

I went to Union Pacific, and they gave me a job right away. I was set, but this job was very unsatisfactory in one way. It was 12 hours a day, seven days a week. But I had to have it. I wanted to stay. I went ahead and took it. I worked there for a couple or three months, but I got awfully sick of it, 12 hours a day. I didn't go anywhere, I didn't do anything, and Sunday came and I felt really funny. I finally thought, "I'm going to quit this job." I decided I'd take a couple of weeks and go to the beach. We really enjoyed the beach. I went down to Sears Roebuck to get a pair of swimming trunks, and while I was there, I happened to pass the shoe department. It dawned on me, "Why not ask them for a job?" I didn't know what kind of a recommend I'd get after quitting a job in Salt Lake, but I walked up to the manager of the shoe department and asked him for a job. He said, "Sure, we can give you a job."

I went to work for Sears Roebuck. I thought I'd have a chance for a little vacation, but I didn't. This was a turning point in my life, working for the shoe department in Sears Roebuck on 9th and Boyle. That's where I met Mary Emily McDonald, my beloved wife.

The reason I got this job was because one of the regular salesmen had a wheat farm in Canada. He had taken a leave of absence for three months and gone up there. I happened along just at the time they needed someone. The manager said, "One of our regulars has gone up to Canada, and you can have his job for three months and fill the vacancy we have." Everything was really fine.

In the meantime, they'd hired another man, a Jewish fellow from Chicago. He was very confident. He figured he had a job even after this other guy came back. He figured he was a big shot.

Mary was a traveling cashier for the Sears Roebuck Stores. She would relieve the cashiers in the various departments. One day she was cashier in the shoe department. The time came for me to go out to lunch, and she said, "Would you like to have me add up your sales tickets while you're out to lunch?"

I said, "That's awfully nice of you. I sure would appreciate that."

At lunch I thought, "You know, it might be possible to get a date with her and go out to West Lake Park, boat riding or something." When I came back, she handed me the slip she'd added up, and I asked her for a date. I said, "How would you like to go out to West Lake Park and go boat riding?"

She said, "I don't want to go out boat riding, but I'll make a date to go out with you."

We started to go together, and it was love at first sight. I know we were predestined to know each other and meet each other.

While I was working at the shoe department, we received word that the fellow who had the wheat farm had passed away. That meant one of us could have a steady job and take his place. Just about this time the Jewish fellow came up to me and said, "Well, what are you going to do, Allred, when you're laid off?" This was during the Depression, and I said, "Well I don't know. I don't know what I'll do."

"Well," he said, "it's tough to be out of a job now." He was so cocky. I thought perhaps he had an inside track and they'd told him he was going to have the job. One Saturday, the manager came to me and said, "You know, Allred, the three months is up." I knew what was coming. I thought, "I guess that's it." He said, "We've got to make arrangements for you to stay. We'll let Stinger go." I almost fell over backwards. The way this fellow talked, I really thought he had the job. Towards quitting time, the messenger boy came. He called, "Mr. Stinger, Mr. Stinger," paging him. He said, "You're wanted up in the superintendent's office." A funny look came over his face. He knew what it was all about. He knew that he was the one to go. He went up to the office and when he came back he said, "This is a one horse-town, and I'm going back to Chicago".

It was quite a thrill to know I had a steady job. It was during the Depression. I worked there for eleven months, then I transferred to the Vermont store in Los Angeles.

Mont kept his job at Goodyear Tire and Rubber, and Eddie was working at Standard Oil in El Segundo. It looked like we were to be in California. Another good friend, Charles Harold, came down. We knew him in Bingham when we were selling insurance. In the mean-time he had married a cousin of mine. Walt Modum, from Roosevelt, came around the same time. We had quite a few acquaintances we used to run with. We had all known each other before we came to California. We met friends and made friends with other fellows when we came.

I started going steady with Mary. We went out real often to the dances. We finally decided to get married in June. This was in the spring of 1929, but when June came around, we didn't have the money to get married. We decided to postpone it until the next June, a year from then.

One beautiful Sunday afternoon we took an airplane ride over Los Angeles. There was an airfield on Western Avenue that is now taken up with industrial buildings, but at that time there was quite an open field just below the golf course, where they did barnstorming. You could take a ride over Los Angeles most any time. We were up in the air flying over Los Angeles, and kind of jokingly I said, "What do you say we fly down to Tijuana and get married?"

Mary said, "We don't have to fly to Tijuana to get married. We can get married anytime."

I said, "Well, what do you say if we land and go look for an apartment and get married?" She said, "O.K." After we landed, we went to her home and told her father and mother that we would get married a week from then, the next Sunday. Everything was all set up. We went out first thing and found a little apartment. That's how we happened to get married the 30th of August.

When I came home and told Montie, he was very, very unhappy. He could see we were splitting up, and he talked and talked, really tried to get me not to do it.

He said, "You and I get along together. You don't want to go and get married."

He talked to me half the night, but I was really determined that I was going to go do this. I tell you he was quite broken up. It wasn't long after that, he and Eddie decided to go back to Utah and Idaho. He quit his job at Goodyear. When he found out I was going to get married, he figured, "I'll pull out and take on a new pal--Eddie."

They went to Utah and to Idaho, and I'll tell you, that was one time in my life I was really lonesome--my brother leaving me. I remember the day they left. I walked around block after block, thinking about how we'd split up the threesome. It was quite an ordeal for me, but I did love Mary.

I said, "I'm going to go ahead and get married and make a life for myself without Montie."

Mont and Eddie went to Idaho and worked on a ranch for a while and had a real good time. They stayed about a year. Then they came back to California and was I happy to see them! In the mean-time I was married, and it was quite different.

Mont and I were working for Goodyear Tire and Rubber. Our names being so much alike, it was difficult for us to get Social Security numbers. The government decided everyone had to have social security numbers. We put in our applications through the company, and it wasn't long until I received mine, but Mont didn't receive his. Goodyear was concerned, because it was the law that we had to have those numbers. They wrote to Washington explaining that Mont Allred hadn't received his Social Security number. They received a letter back saying that they had sent his social security number, but they had received two applications for it (there was Clement and Clemont, you see). They wrote another letter explaining that we were identical twins and that Clement had received his, but Clemont hadn't. They wrote back and said they couldn't issue another social security number unless there was an affidavit signed and pictures taken, definite proof that we were twins. We had our pictures taken (I still have the pictures).

This story came out in the company paper. The Los Angeles Times got a hold of it and put in a little article with our pictures saying that identical twins had difficulty getting Social Security numbers. It wasn't long until Mont got his.

We were selling appliances. Arvil was the sales manager in Provo when we were going to the BYU. Mont and I were selling vacuum cleaners and washing machines, etc., from Salt Lake. We were sending our orders in and signing our names, but they were so much alike that they were giving me credit for all the sales. One day in the Sunday paper, there was an article about a salesman in Provo by the name of Clement Allred who was really doing well. It told how much he'd sold. We got a paper saying I had won an award, and they were sending me a gold watch. Mont was really hurt. He was just as good a salesman as I was, and here I was getting a big spread in the paper. He was very disgruntled. Then we found out they were giving me credit for Mont's work.

We've had things like that happen all our lives. People send bills to me that are supposed to be Mont's, and my bills have gone to him. It's really been a mix-up.

I'd like to tell a story about Jimmy Hanningan. When we found out Mary was pregnant with Patsy, I was teasing Jimmy. He had a girl and I had a girl (Barbara).

I said, "I'm going to have a boy. You know, that's something I don't think you can have. The only difference between you and me is that you give up, and I don't. I'm going to have a boy."

He laughed and said, "When you go to the hospital and have that boy, I want to be the first one you notify." We joked about it. When Mary went to the hospital to have the baby, one of the nurses said, "You have a big fine beautiful baby girl."

I'd promised Jimmy I'd call just as soon as the baby was born. So I did. I said, "We have a new member of the Allred family." "What did you get, a boy or a girl?"

I said, "It's a girl." Patty heard these stories, so when she was growing up, she wanted to be daddy's little boy. As a young girl she could out-run anyone in the neighborhood. She could climb trees and was trying to be a boy because she figured that was what Daddy wanted. What a joy little Patsy was.

When Mary was in the hospital, Mont and I went down to see the baby, and we took Barbara Ellen with us. Mont was tending Barbara Ellen, and she got away from him. She was two years old, and she running up and down the halls, really having a time. Montie was chasing her up and down the hall. He was having quite a time.

When Patsy was about a year old, we had an Allred reunion. Mary and Mont and I went up to the reunion. Mont had married Irene. When we were coming into St. George, Utah, Mont said in a joking way, "Now I'd think I better drive."

Irene said, "Why?"

"We're in Utah now, and if we hit anyone here it's bound to be a relative, so I'd better drive."

We went on to Fillmore, where our mother's folks are from, where my grandfather came in pioneer days. There are a lot of my mother's relatives in Fillmore. We stopped and went to one of our cousins. When our relatives found out that the twins had come from California, you should have seen the different ones who came to see us. Irene couldn't believe it. Mary couldn't believe it--so many relatives. Half the town were Brunsons. We went on to Salt Lake and had a wonderful reunion there.

Barbara used to be afraid of the vacuum cleaner. When she was a baby she'd be practically hysterical. We had tried to get her over it by having her stand there while we'd turn on the vacuum so she could see there was nothing to be afraid of. When we arrived in Provo, Barbara was three years old. She was a cute little vixon. We were busy greeting each other, and when we looked up, Barbara had disappeared. Nobody knew where she was. We couldn't find her (we hadn't noticed her go), and so we went looking for her. I looked down one side of the street and somebody went down the other side. We asked, "Did you see a little three year old girl, a little blond?"

They'd say, "No." Finally we went to a place and I knocked on the door and said, "You didn't happen to see a little girl?"

The lady said, "Oh yes, she's here. Do you know what happened? She came to the door and said 'Do you have a vacuum cleaner?' And I said, 'Yes I do.' And she said, 'Can I listen to it?'"

I picked her up and brought her back to where we were staying.

At this time in my life, I took up golf. It has been one of the most wonderful sports I have ever participated in. Mont and I played two or three days a week and never had a lesson in our lives. We both had the ability to swing the club.

We went to the old Sunset Golf Tee Course, rented some clubs, and started to play. We loved the game. I don't mean to brag, but we became good golfers. I believe, if we had taken up golf when we were young, we could have had quite a name. I have quite a few trophies and so has Mont. This is where Mont met Dorothy, his second wife.

Before I forget, I'm going to tell a little story about golf. We were having a golf tournament, and Louis (my brother) came down from Utah. When he arrived, he asked where we were. Barbara and Pat said we were playing golf.

He said, "Would you like to go with me out to see them?"

They came out to the golf course. Just ahead of us on the fairway was a fellow, playing for the playoff.

Barbara and Pat yelled out, "Daddy, Uncle Louis is here!" This fellow had just bent down to putt when he heard them call out. He straightened out, got down again and he heard, "Daddy, Uncle Louis is here." Then he bent down, putted and he landed it in!

He looked up with a big smile on his face and said, "Well that's for Uncle Louis." After we got back to the clubhouse he said, "I want to meet Uncle Louis." He was a good friend of ours and knew Pat and Barbara.

At one time, Mary was very ill with pneumonia. We almost lost her. At the same time, her mother and I were in an automobile accident. A fellow pulled in front of me and, when we crashed, her mother was thrown through the windshield. At first Mary wasn't told her mother was in the hospital. Mary wasn't expected to live.

The doctor said, "By no means, let her know her mother is in the hospital. You keep it quiet, because we don't want her to worry about anything until she's better."

I hated to spring a surprise on her like that. But I had to keep that promise. I had to be quite a liar. That was quite an ordeal for me.

When Mary was in the hospital, I wanted to encourage her, so I said, "You get well and we'll buy a home."

I had a good job and we were getting along pretty good. She never forgot that, so in 1940, on the 4th of July holiday, Mary said, "Let's get the kids and go to the beach."

We got in the car and went to Hawthorne. On Imperial Highway, as you go to the beach, they were building a new tract of homes. I said, "Let's go by here and look at these new homes." Unknown to me, she had been out there and picked out a home she liked. Not only that, but she had an appointment with a salesman to be there. When we pulled up and there was a salesman standing there I realized this was a set up. We got out and he showed us the place. They had five different types of homes. He said there were others. I said, "No, if Mary likes this one, there's no use looking further."

The price was 27,000 dollars, a lot of money. It was 50 dollars down and 20 dollars a month.

I said, "I don't have 50 dollars."

He said, "How much money do you have?"

I said, "5 dollars."

He said ,"You give me that $5.00 and sign a note for the 40."

That's how we got in our home. Well, my lands, you couldn't beat that! We've been in it for thirty years.

We were the first ones to buy a home in that tract and the first ones to move in. The girls were four and six. A short time later a family with three girls moved in. We really enjoyed them. These kids grew up together.

Then the war came along. You couldn't work in anything but defense work. I went to the ship yards to Consolidated Steel for about 18 months.

Then I went over to Western Pipe and Steel. I went to a blue print school. At a certain time of day the employees could go to school and learn to read blue prints.

The war finally ended, and I went to an appliance store in Torrance and worked for Charles Ray, selling. Television started and I was really interested in selling television. Then the Korean war came on.

When the war started, we couldn't get merchandise. The years went by and the lady next door, Lois Demary, was working at Alcoa as a timekeeper. Her husband was also working in the plant. They were in need of a timekeeper, and Lois came to Mary and said, "There's a time-keeping position open, and I'm sure if you go down and apply you can get the job."

Mary asked me if I'd drive her downtown to Alcoa to check on this job. I called up the store and told my boss I'd be late. Mary and I went down to Alcoa and went into the personnel office. It was full of a variety of people, but I was all dressed up like I was when I worked in the store. When the manager came out he said, "I'm sorry, but there's no hiring today." He looked over and saw Mary and a couple of women and he said, "There's nothing for women at all." Then he winked at me. I wondered what it was about, so Mary left and I stayed.

He came up and said, "Is there anything I can do for you?"

I said, "What do you mean?"

He said, "Are you interested in a job?"

"I'm always looking for opportunities." (We couldn't get merchandise at the store where I worked.) If I could get a job there until the Korean war was over, I'd be alright.

He said, "We need a timekeeper. Would you be interested?" "I'm open for opportunities."

"Well," he said, "I'll call the chief timekeeper and have him come and talk to you."

I said, "O.K." All this time, Mary was out in the car waiting for me. The timekeeper came and told me what a beautiful job it was, and the pay was pretty good. I could retire on it, and he really sold me. They gave me the job. Mary was waiting for me, and when I arrived, she said, "What in the world happened to you? Where have you been?"

I said, "I got a job."

"What do you mean?"

"I'm going to be a timekeeper." It was the job she had gone down to get.

She smiled and said, "I'll never take you to go looking for a job again."

That was the beginning of my career at Alcoa of America. In the meantime, Barbara was married. Bill had been in Korea about a year, and they were married when he came back.

During the war, Mary had taken care of children while their parents worked. There was one little boy whose mother brought him when he was about three months old, and what a beautiful baby he was. He had big brown eyes, and we really fell in love with him. One night I came home from the shipyards and Mary was standing in the door. She had this baby in her arms and she said, "How would you like to adopt Don?"

I said, "I would love that. Is there any possible chance?" She said, "Yes. An attorney for the state came by and said Don was going to be put up for adoption and wanted to know if we would adopt him."

I was surely happy about that, and you can imagine Barbara and Pat felt--how happy they were. The state checked for about a year on how we took care of him, and they went into our past history. When the final adoption came through (he was really a cute baby), we took him to court. We had a well- known lady judge (quite an old lady) who had been in Los Angeles a long time. We were supposed to be quiet, but when they brought up the Allred adoption you should have heard Barbara and Pat! Boy! They really made a noise. They were overjoyed. The judge told them to "be quiet, now," but she was so pleased they loved him so much. She looked down over her glasses (she had a pointed nose) and said, "He's a dear little fellah, isn't he?" We were so happy when we brought him home and he was our own little boy. We had the papers made out that stated he was born to us.

He had real dark brown eyes and dark hair and these two little girls with blonde hair just mothered him when we took him to church. They'd say, "This is our little brother."

As he grew into boyhood, he was very cute. I got him a little tractor, and we'd go down with him down the block. It wasn't long until he wanted to go by himself. He'd say, "Now wait here and I'll be right back," and he'd go around the block on his tricycle. He was so happy, with a big grin on his face.

I had a pet name for him. I loved him, and I'd call him Tweedlebomb or Stinklestime, in a teasing way. I'd call out "Tweedlebomb!" And I could hear his little feet coming to me. He'd also answer to Stinklestime. I'd ask him what his name was and he'd say Tweedlebomb Stinklestime. He didn't mind at all. He surely was a darling boy, so beautiful.

When Barbara and Pat were quite young, we had an old tom cat. He was a great big huge cat, an old fighter, and he seemed to think we belonged to him. We got him when we first moved into the tract, and he ran all the other cats off. He'd be out all night fighting. I've seen him a mile and a half away from our home, while I've been driving along in the car. He was blind in one eye. One April Fool's morning (Pat and Barbara were still in bed), I got up and came in and said, "Do you know what happened last night?"

These two little girls looked up and said, "No, Daddy, what happened?"

"Well," I said, "you know, Old Tom had kittens."

"Oh no, is that so?"

Old Tom was sleeping out on the back porch and he'd been out all night. They got up and asked, "Where is he?"

I said, "He's out on the back porch." They went out, but they couldn't see any kittens. They said, "We don't see any kittens." And of course, I said "April's Fool."

Well, I'll never forget how for two or three days these kids pulled jokes on me--trying to get even. They put salt in the food and everything they could think of.

When Barbara was about fifteen years old, we were having a little bit of fun. Barbara said something about how she could do anything as good as I could. I said, "Oh you think so? If you want to, I can prove to you that I can do anything you want to do."

She asked, "What will we do?"

I said, "We'll have a foot race." I went out in the street and stepped off a hundred yards. Barbara had one of her very good friends, Chris Nielson, there. They were planning to go to the mountains, but I said, "Come on now, we'll have this foot race." The neighborhood could see what was going on, so they came and lined up like they used to on the 4th of July when we were kids. We started this race, and away we went. I tell you, Barbara was running so close to me (I was running as fast as I could) and I'd be looking behind me. I couldn't even see her. She was so close! But I won the race.

We'd had a little bet. I said, "I won this race, so you can't go up to the snow, up to the mountain. If you had won, I'd have had to do the dishes for a week." Barbara took it real well, but her friend was quite upset. When the time came, of course I said, "You go ahead," but we had quite a foot race.

We had neighbors, the DeMarys. Peggy DeMary was just about the same age as Pat. When she was a little girl, she came over to show us her Easter basket, and she was so proud! She knocked at the door and when I answered it, here was this little girl with big blue eyes and she had a beautiful Easter basket. She held it up to show me.

I said, "Well, Peggy, Peggy! My goodness! How wonderful it is to have you, of all people, bring me a lovely Easter basket like that! Mary, come here and see what Peggy brought me!"

She looked like she was about to cry. I took the basket, and I just flattered her! I said, "That's the sweetest thing anybody ever did!"

I'll never forget her expression. After a little while, of course, I gave it back.

I used to borrow money from her. She'd come over and I'd say, "Peggy, do you have any money at all?"

She'd say, "Well . . . I have a dollar."

And I'd say, "Do you think I could borrow about fifty cents? I know you've got it, because you just told me. If I had money and you asked me, I'd let you have it. Do you think I could borrow that for a little while?"

I'd borrow money from her, and she would reluctantly do it. She didn't want to hurt my feelings. I'd give the money back later, you know, with a little interest. Those were really happy days.

We had another young lady right about the same age. Her name was Ilene Cook. They'd just had a brand new baby, and she came over, one time, to tell me about her little baby sister.

I said, "Well now, Ilene, I know that you have that little baby, and I'd like to make a little trade with you. We've got a big beautiful tom cat here. He's blind in one eye, but he can see alright." I said, "I'd like to trade him for the baby."

Oh, she was flabbergasted! She said, "I should say not!"

I said, "Well, has your little baby sister got any teeth?"

She said, "No."

I said, "Well, Tommy's got teeth." I said, "Has your little sister got any hair yet?"

"No."

"Well, Tommy has."

She went back home half crying and told her mother that Mr. Allred was trying to make a trade with her--the baby for the old tom cat. Of course in the neighborhood they all knew me for an old tease, but I had a good time with these kids.